|

The Family of Winton

In the early history of the Seton

family, the lands of Winton were granted by Royal Charter by King to Philip de

Setoune. Philip succeeded to

Seher, his father and got a charter from

King William the Lion, in 1169, confirming to him certain lands, which remained

in possession of his descendants for more than five hundred years. It is one of

the oldest Scottish charters in existence, and is mentioned with enthusiasm by

the learned Cosmo Innes (Scotland in the Middle Ages, p. 20), who says: "I could

not give you a better specimen of one of those ancient simple conveyances than a

charter of William the Lion, a grant to the ancient family of Seton. It conveys

three great baronies, confers all baronial privileges, fixes the reddendo at one

knight's service, expresses the formal authentication of a goodly array of

witnesses, and is comprised in seven short lines. The original is in possession

of the Earl of Eglinton and Winton. From Philip stems the family of Winton,

and in the style of the times, his son took as their family name that of their estate. Sources: "The History of the House of Seytoun to the Year MDLIX", Sir Richard Maitland of Lethington, Knight, with the

Continuation, by Alexander Viscount Kingston, to MDCLXXXVII. Printed at Glasgow,

MDCCCXXIX. "A History of the Family of Seton during Eight Centuries" George

Seton, Advocate, M.A. Oxon., etc. Two vols. Edinburgh, 1896"An Old Family"

Monsignor Seton, Call Number: R929.2 S495

In the year 1347, Lady Margaret

Seton was forcibly abducted by a neighboring baron named Alan de Winton, a distant

kinsman of her own and a cadet of the Seton family. Andrew Wyntoun relates the

case in his Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland, saying: "Dat yhere Alene de Wyntoun

tuk the yhoung Lady Setoun and weddit hyr than till hys wyf." This outrage

caused a bloody contest in Lothian; on which occasion, says Fordun, a hundred

ploughs were laid aside from labor.

A romantic incident of this affair--the opposition springing, perhaps, from

selfish motives on the part of her guardian--is that when Margaret was rescued

and Alan confronted with the Seton family, she was handed a ring and a dagger,

with permission to give him either Love or Death. She gave him the ring, and

they were happy ever afterward. Alan de Winton assumed his wife's name,

and died in the Holy Land, leaving besides a daughter Christian de Seton who

became Countess of Dunbar and March, three sons: 1st Sir William Seton,

his successor and 1st Lord Seton; 2nd Alexander Seton who married Jean

Halyburton, daughter of Sir Thomas Halyburton of Dirleton (recorded by Alexander

Nisbet); and Henry who retained his father's name and inherited Wrychthouses (Wrightshouses,

Edinburgh).

One of the oldest stones of this mansion bears the Seton's arms. In the year 1347, Lady Margaret

Seton was forcibly abducted by a neighboring baron named Alan de Winton, a distant

kinsman of her own and a cadet of the Seton family. Andrew Wyntoun relates the

case in his Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland, saying: "Dat yhere Alene de Wyntoun

tuk the yhoung Lady Setoun and weddit hyr than till hys wyf." This outrage

caused a bloody contest in Lothian; on which occasion, says Fordun, a hundred

ploughs were laid aside from labor.

A romantic incident of this affair--the opposition springing, perhaps, from

selfish motives on the part of her guardian--is that when Margaret was rescued

and Alan confronted with the Seton family, she was handed a ring and a dagger,

with permission to give him either Love or Death. She gave him the ring, and

they were happy ever afterward. Alan de Winton assumed his wife's name,

and died in the Holy Land, leaving besides a daughter Christian de Seton who

became Countess of Dunbar and March, three sons: 1st Sir William Seton,

his successor and 1st Lord Seton; 2nd Alexander Seton who married Jean

Halyburton, daughter of Sir Thomas Halyburton of Dirleton (recorded by Alexander

Nisbet); and Henry who retained his father's name and inherited Wrychthouses (Wrightshouses,

Edinburgh).

One of the oldest stones of this mansion bears the Seton's arms.

Henry de

Winton married Amy Brown of Coalston and continued the family name of Winton.

Henry was one of the heroes of Otterburn, August 19, 1388. Friossart calls

him :The Seigneur de Venton" (Wintoun, Francisque Michel). Sources: "The

History of the House of Seytoun to the Year MDLIX", Sir Richard Maitland of

Lethington, Knight, with the Continuation, by Alexander Viscount Kingston, to

MDCLXXXVII. Printed at Glasgow, MDCCCXXIX. "A History of the Family of Seton

during Eight Centuries" George Seton, Advocate, M.A. Oxon., etc. Two vols.

Edinburgh, 1896 "An Old Family" Monsignor Seton, Call Number: R929.2 S495.

From Henry de Winton was descended the famous Scottish chronicler, Andrew

Wyntoun, who is credited as being Scotlands first historian.

From the Winton's of Wrychthouses

stems the Scottish family of Winton, and the estate of Wrychthouses was to

remain with them until it was sold to the Napier family. The estate is

listed in

Blaeu's Atlas of Scotland, 1654

compiled by David

Buchanan, 1595-1652.

The lands of the

estate of Wrightshouses are found between the Water of Leith and the North Esk

there are very many houses and castles of nobles worthy of mention. First

between the Water of Leith and the Braid Burn, starting from the foot of the

Pentland Hills and continuing the descent to the north as far as the Forth, are

Swanston, Comiston, Craiglockhart, Craighouse, Braid, Plewlands, Bruntsfield,

Grange, Sciennes, Wrightshouses, Merchiston, Priestfield, Dalry, Coates, Drum,

Broughton, Pilrig, Restalrig, and Duddingston.

The Wrychtishousis (Wrightshouses) estate, in Edinburgh, lay

to the west of the Biggar Road just to the south of Tollcross at the beginning

of the district now known as Bruntsfield. The name is recorded in a charter

dated 1382, but the oldest inscription noted in the walls of the mansion dated

from the Seton-Winton's tenure, anno 1376. The estate was acquired by a William Napier sometime between 1390

and 1406. The origin of the name is not certain, it could be "houses of

wrights or carpenters" but considering its rural location in the 14th

century, nearly two miles outside the city walls, it seems unlikely. It is more

likely to have been named after an owner called Wright.

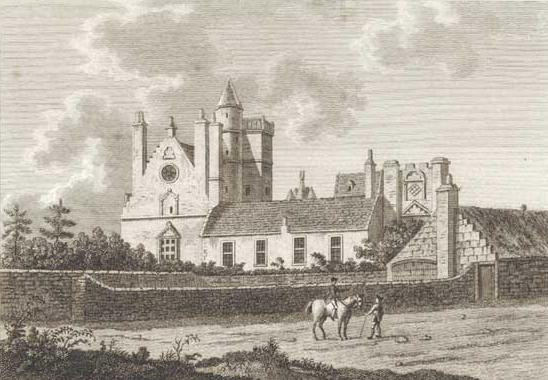

From the "Antiquities of Scotland", the

mansion-castle was noted as:

THE WRYTE's HOUSES.

THE Wryte's Houses stand a small distance south-west of the town

of Edinburgh, in a suburb called Portsborough. Their

denomination is vulgarly, but erroneously, said to have

originated from their having been the residence of certain

Wrights or Carpenters, employed in cutting down and working the

oaks and other timber growing on the Borough Muir ; but

Maitland, who mentions this, says they were houses belonging to

the Laird of Wryte. The western wing of this building, according

to him, is the most ancient part of the edifice, having on it an

inscription bearing date anno 1316. The

wing at the eastern side was, as is related, built in the reign

of king Robert III. and the centre building, connecting them,

was erected in the reign of king James VI. but Arnot says this

house was built for the reception of a mistress of king James

IV. This he seems to affirm of the whole building.

IN 1788, when this View was taken, they had been just repaired,

and deformed with a daubing of lime or whitewash, and had,

besides, been otherwise much injured in their appearance, by the

modernizing of the windows of the centre building, which before

agreed with the style of the wings.

All

that remains of the old castle or mansion of the Winton's line

of Wrychthouses.

From the "Carpenter Gothic".

Gillespies Hospital, built on the site of the picturesque ancient mansion of

Wrighthouses, demolished to make room for it by the Trustees of James Gillespie,

snuff maker. Built 1806.

Used as soldiers quarters during the War.

click to read:

Alexander Winton, Motorcar Manufacturer

The Scottish chronicler, born (as we know from the

internal evidence of his writings) in the reign of David II, about the middle of

the fourteenth century. He was related to Alan of Wyntoun, who married the

heiress of Seton, and is now represented by the Earl of Eglinton and Winton. He

became a canon-regular of the priory of St. Andrews, and before 1395 was

appointed prior of the ancient monastery of Lochleven, in Kinross-schire, which

was a subject house of St. Andrews for upwards of four hundred years (see

LOCHLEVEN). Innes, in his "Critical Essay" (1729), pointed out that the register

of the priory of St. Andrews contained several acts or public instruments of

Wyntoun, as prior of Lochleven, from 1395 to 1413; but there is no evidence as

to how long he continued in office after the latter year, or as to the date of

his death. It was at the request of Sir John de Wemyss (ancestor of the Earls of

Wemyss), whom he mentions as one of his intimate friends, that Wyntoun undertook

to write his "Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland", so entitled, as he himself

explains, not because it was his own composition, but because it begins at the

beginning of things, namely with the creation of

angels. How long the compilation of the work took is

uncertain, but the fact that Robert, Duke of Albany, is mentioned in it as dead

proves that it was finished some time after September, 1420. The author, while

engaged in the latter part of it, reckoned himself already an old man, as

appears from his prologue to the ninth book, so that it is not probable that he

lived long after its completion. The variations in the manuscripts show that it

was frequently revised and corrected, in all probability by Wyntoun's own hand.

No printed edition of the Chronicle appeared until 1795, when

it was edited from the Royal manuscript in the British Museum, with a valuable

critical introduction, by David Macpherson. Nearly one- third of the original

was, however, omitted, and this was restored by Laing in his edition published

in 1872, in the "Historians of Scotland" series. Laing describes the eleven

manuscripts of the Chronicle known to exist, and the Scottish Text Society has

since printed a new edition from the Cottonian and Wemyss manuscripts, with the

variants of the other texts. A considerable portion of the Chronicle, it must be

noted, is the work of an unknown author, who sent it to Wyntoun, and it was

incorporated by him into his own narrative. Both are written in the same

easy-flowing, octosyllabic rhyming verse, and the work has therefore value from

a poetical as well as from an historical standpoint. Andrew Lang credits Wyntoun

with "a trace of the critical spirit, displayed in his wrestlings with feigned

genealogies"; but Æneas Mackay does him more justice in pointing out that he

understands the importance of chronology, and is, for the age in which he wrote,

wonderfully accurate as to dates. His work has thus real value as the first

attempt at scientific history writing in Scotland, and philologically it is not

less important as having been written in the Scots vernacular, and not (like

nearly all the works of contemporary men of learning) in a dead language.

Regarded as a poet, Wyntoun can hardly take high rank, certainly not equal rank

to his predecessor Barbour, the father of Scottish poetry. His narrative, in

truth, though written in rhyme is mostly prosaic in style; but some of his

descriptions are vivid, and touched with the true spirit of poetry.

"In Wyntown’s

Chronicle," says Mr Macpherson, "the historian may find, what, for want of more

ancient records, which have long ago perished, we must now consider as the

original accounts of many transactions, and also many events related from his

own knowledge or the reports of eye-witnesses. His faithful adherence to his

authorities appears from comparing his accounts with unquestionable vouchers,

such as the Federa Angliae, and the existing remains of the ‘Register of

the Priory of St Andrews,’ that venerable monument of ancient Scottish history

and antiquities, generally coeval with the facts recorded in it, whence he has

given large extracts almost literally translated." His character as an historian

is in a great measure common to the other historical writers of his age, who

generally admitted into their works the absurdity of tradition along with

authentic narrative, and often without any mark of discrimination, esteeming it

a sufficient standard of historic fidelity to narrate nothing but what they

found written by others before them. Indeed, it may be considered fortunate that

they adopted this method of compilation, for through it we are presented with

many genuine transcripts from ancient authorities, of which their extracts are

the only existing remains. In Wyntown’s work, for example, we have nearly three

hundred lines of Barbour, in a more genuine state than in any manuscript of

Barbour’s own work, and we have also preserved a little elegiac song on the

death of Alexander III., which must be nearly ninety years older than Barbour’s

work. Of Barbour and other writers, Wyntown speaks in a generous and respectful

manner, [He even avows his incompetency to write equal to Barbour, as in the

following lines:-- The Stewartis originale, The Archdekyne has tretyd hal, In

metre fayre mare wertwsly, Than I can thynk be my study, &c. –Cronykil, B. viii.

c. 7. v. 143.] and the same liberality of sentiment is displayed by him

regarding the enemies of his country, whose gallantry he takes frequent occasion

to praise. Considering the paucity of books in Scotland at the time, Wyntown’s

learning and resources were by no means contemptible. He quotes, among the

ancient authors, Aristotle, Galen, Palaephatus, Josephus, Cicero, Livy, Justin,

Solinus, and Valerius Maximus, and also mentions Homer, Virgil, Horace, Ovid,

Statius, Boethius, Dionysius, Cato, Dares Phrygius, Origen, Augustin, Jerome, &c

Wyntown’s

Chronicle being in rhyme, he ranks among the poets of Scotland and he is in

point of time the third of the few early ones whose works we possess, Thomas the

Rhymer and Barbour being his only extant predecessors. His work is entirely

composed of couplets, and these generally of eight syllables, though lines even

of ten and others of six syllables frequently occur. "Perhaps," says Mr Ellis,

"the noblest modern versifier who should undertake to enumerate in metre the

years of our Lord in only one century, would feel some respect for the ingenuity

with which Wyntown has contrived to vary his rhymes throughout such a formidable

chronological series as he ventured to encounter. His genius is certainly

inferior to that of his predecessor Barbour; but at least his versification is

easy, his language pure, and his style often animated."

He

wrote it in the Scottish tongue, was an older contemporary of Walter Bower. He

died an old man soon after 1420. Of him, as of the other contemporary

chroniclers, we know little except that he was head of St. Serf’s priory in

Lochleven, and a canon regular of St. Andrews, which, in 1413, became the site

of the first university founded in Scotland. The name of his work, The

Orygynale Cronykil, only means that he went back to the beginning of things,

as do the others. Wyntoun surpasses them only in beginning with a book on the

history of angels. Naturally, the early part is derived mostly from the Bible,

and The Cronykil has no historical value except for Scotland, and for

Scotland only from Malcolm Canmore onwards, its value increasing as the author

approaches his own time. For Robert the Bruce, he not only refers to Barbour but

quotes nearly three hundred lines of The Bruce verbatim—thus being the

earliest, and a very valuable, authority for Barbour’s text. in the last two

books, he also incorporates a long chronicle, the author of which he says he did

not know. From the historical point of view, these chroniclers altogether

perverted the early chronology of Scottish affairs. The iron of Edward I had

sunk deep into the Scottish soul, and it was necessary, at all costs, to show

that Scotland had a list of kings extending backwards far beyond anything that

England could boast. This it was easy to achieve by making the Scottish and

Pictish dynasties successive instead of contemporary, and patching awkward flaws

by creating a few more kings when necessary. That the Scots might not be charged

with being usurpers, it was necessary to allege that they were in Scotland

before the Picts. History was thus turned upside down.

Apart from the

national interests which were involved, the controversy was exactly like that

which raged between Oxford and Cambridge in the sixteenth century as to the date

of their foundations, and it led to the same tampering with evidence. Wyntoun

has no claims to the name of poet. He is a chronicler, and would himself have

been surprised to be found in the company of the “makaris.”

The original scheme was for seven

books, but the work was, later, extended to nine. Wyntoun would not have

been the child of his age and training did not the early part of his history

contain many marvels. We hear how Gedell-Glaiss, the son of Sir Newill, came out

of Scythia and married Scota, Pharaoh’s daughter. Being, naturally, unpopular

with the Egyptian nobility, he then emigrated to Spain and founded the race

which, in later days, appeared in Ireland and Scotland. It is interesting to

learn that Wyntoun identified Gaelic and Basque, part of the Scottish stock

remaining behind in Spain.

And Simon Brek it was that first brought the Coronation

Stone from Spain to Ireland. The exact date before the Christian era is given

for all these important events. When Wyntoun arrives at the Christian

dispensation and the era of the saints, it is only natural that he should dwell

with satisfaction on the achievements of St. Serf, to whom his own priory was

dedicated. St. Serf was the “kyngis sone off Kanaan,” who, leaving the kingdom

to his younger brother, passed through Alexandria, Constantinople and Rome.

Hence, after he had been seven years pope, his guiding angel conducted him

through France. He then took ship, arrived in the Firth of Forth and was advised

by St. Adamnan to pass into Fife. Ultimately, after difficulties with the

Pictish king, he founded a church at Culross, and then passed to the “Inche of

Lowchlewyn.” That he should raise the dead and cast out devils was to be

expected. A thief stole his pet lamb and ate it. Taxed with the crime by the

saint he denied it, but was speedily convicted, for “the schype thar bletyt in

hys wayme.” 52

Wyntoun tells, not without sympathy, the story of that “Duk of Frissis,” who,

with one foot already in the baptismal font, halted to enquire whether more of

his kindred were in hell or heaven. The bishop of those days could have but one

answer, whereupon the duke said

With all his

credulity, Wyntoun, in the later part of his chronicle, is a most valuable

source for the history of his country. To him and to Fordun we are indebted for

most of our knowledge of early Scotland, since little documentary evidence of

that period survived the wreck that was wrought by Edward I.

|

|

|

Withe thai

he cheyssit 53

hym to duel, |

|

And said

he dowtyt for to be |

|

Reprewit

wnkynde gif that he |

|

Sulde

withedraw hym in to deide 54 |

|

Fra his

kyn til ane wncouthe leide, 55 |

|

Qwhar he

was nwrist and bred wp withe, |

|

Qwhar

neuir nane was of his kyn, |

|

Aulde na [char]onge,

mare na myn, |

|

That neuir

was blenkyt withe that blayme. |

|

“[Abrenuncio] for thi that schayme,” |

|

He said,

and of the fant he tuk |

|

His fute,

and hail he thar forsuyk |

|

Cristyndome euir for to ta, 56 |

|

For til

his freyndis he walde ga |

|

Withe

thaim stedfastly to duell |

|

Euirmare

in the pyne of hel. 57 |

|

Good churchman as Wyntoun is, he is not slow to tell of

wickedness in high places and duly relates the story of pope Joan, with the

curious addition

|

|

|

Scho was

Inglis of nacion |

|

Richt

willy of condicion |

|

A burges

douchtyr and his ayre |

|

Prewe,

pleyssande and richt fayr; |

|

Thai

callit hir fadyr Hob of Lyne. 58 |

|

In this book (chap. 18) he also tells the most famous of all

his stories—Macbeth and the weird sisters, and the interview between Malcolm and

Macduff. But Wyntoun renders Macbeth more justice than other writers,

|

|

|

[char]it

in his tyme thar wes plente |

|

Off gold

and siluer, catall and fee. 59 |

|

He wes in

iustice rycht lauchfull, |

|

And till

his liegis rycht awfull. 60 |

|

Birnam wood comes to Dunsinane, and Macbeth, fleeing

across the Mounth, is slain “in to the wod of Lumfanane.” 61

With all his credulity, Wyntoun, in the later part of his chronicle, is a most

valuable source for the history of his country. To him and to Fordun we are

indebted for most of our knowledge of early Scotland, since little documentary

evidence of that period survived the wreck that was wrought by Edward I.

There are various

manuscripts of Wyntown’s work, more or less perfect, still extant. The one in

the British

Museum is the oldest and the best; and after it rank, in antiquity and

correctness, the manuscripts belonging to the Cotton Library and to the

Advocates’ Library at Edinburgh.

|

|