|

The Family of Tytler

(work-in-progress)

The surname of a family distinguished

in law and in the

literature of Scotland, one branch of which

possesses

the estate of Balnain, Inverness-shire, and another that of Woodhouselee,

MidLothian, -- the “haunted Woodhouselee” of Sir Walter Scott’s ballad of ‘The

Gray Brother.’ The surname of a family distinguished

in law and in the

literature of Scotland, one branch of which

possesses

the estate of Balnain, Inverness-shire, and another that of Woodhouselee,

MidLothian, -- the “haunted Woodhouselee” of Sir Walter Scott’s ballad of ‘The

Gray Brother.’

The family name originally was Seton, that of Tytler having been assumed

by the ancestor of the family, a cadet of the noble

house of Seton, founded by a

son of Lord Seton, who temp.

James IV., in a sudden quarrel at a hunting match slew a gentleman of the

name of Gray, fled to the

northern parts of Scotland before fleeing further to

France and changing his name to Tytler.

He later emerged bearing the name and though recognized as a Seton after the

troubles had ended, retained the name of Tytler and thus flourished this family. His two sons returned to

Scotland in the train of

Queen Mary in 1561, and from the elder, the families of Balnain and

Woodhouselee descend. The family name originally was Seton, that of Tytler having been assumed

by the ancestor of the family, a cadet of the noble

house of Seton, founded by a

son of Lord Seton, who temp.

James IV., in a sudden quarrel at a hunting match slew a gentleman of the

name of Gray, fled to the

northern parts of Scotland before fleeing further to

France and changing his name to Tytler.

He later emerged bearing the name and though recognized as a Seton after the

troubles had ended, retained the name of Tytler and thus flourished this family. His two sons returned to

Scotland in the train of

Queen Mary in 1561, and from the elder, the families of Balnain and

Woodhouselee descend.

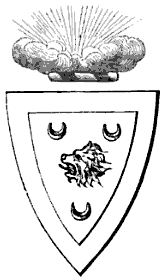

The ancestor of the

Fraser-Tytlers of Belnain are written more

clearly that they are cadet of the family of

Seton, who, having slain a gentleman of the name

of Gray, in a quarrel at a hunting-match during

the reign of James IV, fled to France and

assumed the surname of Tytler, which his

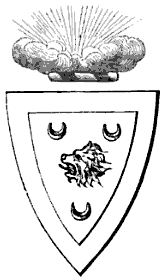

posterity retained. The armorial bearings of the

family are considered to bear reference to these

circumstances—the first and fourth quarters of

the escutcheon being gules, between three

crescents, or (the ensigns of the Setons), a

lion's head, erased, argent, within a bordure of

the second. Crest—the rays of the sun issuing

from behind a cloud, with the motto, " Occultus

nou extinctus."

In his review of Burgon's Memoir of Patrick

Fraser Tytler, Mr. Haunay questions the origin

of the historian's family as stated in the text.

The biographer, he says, "assumes the truth of

the tradition, that the Tytlers descend from a

brother of the George, third Lord Seton, who

fell at Flodden. But it happens that we have

particular information about the Setons of that

period in the quaint old book, The IIUtory of

the House of Seytoun, by Sir Richard Maitland of

Lcthington, whose mother was one of the family,

and who wrote in the sixteenth century. He is

very particular in telling whatever is curious

about the House . . . and must have known so

singular a circumstance as the one recorded by

way of accounting for the change of name from

Seton to Tytler, and if he had known it would

have stated it, which ne nowhere does. We feel

sure, therefore, that, whatever was the origin

of the tradition in question, it is not true in

the form in which theTytlers accept it."—Essays

from the Quarterly, p. 369.

The author is informed by his friend, the

present representative of the family of

Woodhouselee, that it appears, from a very

distinct and circumstantial memorandum, dated

1738, in the handwriting of his great - great -

grandfather (Alexander Tytler), that his family

claim descent, not from " George, third Lord

Seton," as inferred by Mr. Haunay, but from his

chaplain, who was a paternal relative. It

further appears, that the chaplain was the

person referred to in the text who slew Gray in

the hunting-match, and fled to France, whence

two of his sons came to Scotland with Queen

Margin 1561, from one of whom (who settled in

the neighbourhood of Kincardine) the family of

Woodhouselee are lineally descended.

The designed landscape surrounding the mansion house at

Woodhouselee (NT26SW 4.00) was never very large and its full

extent is probably depicted on the 1st edition of the OS 6-inch

map (Edinburghshire 1854, sheet 12). The house stood on the S

side of an un-named stream, its wooded banks forming the N side

of the policies, and the lower, wooded slopes of Woodhouselee

Hill the W side. To the E and S the policies were defined by

shelter-belts enclosing improved fields and parkland.

Most of the elements of the designed landscape still survive,

though the deciduous woodland on the N has largely been replaced

by conifers. Of the features depicted within the policies on the

1st edition of the map, nothing is now visible of a summer-house

(CDTA05 237), which stood in the SW corner of the polices, and

its site is now obscured by a heavy cover of rhododendron. Two

pedestals (CDTA05 2, 238) are shown close to the NW corner of

the policies, but only one (CDTA05 2) survives, standing in

woodland, its E face inscribed with ancient Greek text and the W

with Latin. Nothing is now visible of the footbridge (CDTA05

239) that crossed the stream about 20m N of this pedestal.

None of these features are subsequently shown on the 2nd edition

of the map (Edinburgh 1895, sheet VII.SE). The Fraser Tytler

Memorial (NT26SW 39), which stands in the SW corner of the

policies, was erected in 1893, the year after the survey for the

2nd edition map. The only other structure now visible within the

former policies is some form of wooden building, the collapsed

remains of which lie in the corner of a paddock about 100m E of

the memorial.

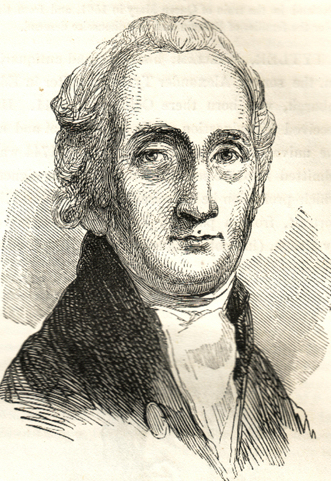

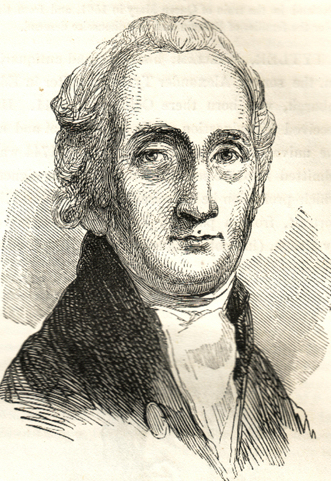

WILLIAM TYTLER, historian and antiquarian, the son of Alexander Tytler, a

writer in Edinburgh, was born there October 12, 1711. He received his education

at the

High School and at

the university of his native city, and in 1744 was admitted into the

society of writers to the signet, which profession he exercised till his death.

His portrait, from a painting by Raeburn, engraved by Beugo (In Scots Magazine,

vol. lxiii.), is subjoined:

ALEXANDER FRASER

TYTLER, Lord Woodhouselee, was born in

Edinburgh, on the 15th of

October, 1747.

He was the eldest son of William Tytler, esquire of Woodhouselee, by his wife,

Anne Craig. The earlier rudiments of education he received from his father at

home; but in the eighth year of his age, he was sent to the High School, then

under the direction of Mr Mathison. At this seminary, young Tytler remained for

five years, distinguishing himself at once by the lively frankness of his

manners, and by the industry and ability with which he applied himself to, and

pursued his studies. The latter procured him the highest honours of the academy;

and, finally, in the last year of his course, obtained for him the dignity of

dux of the rector’s class. ALEXANDER FRASER

TYTLER, Lord Woodhouselee, was born in

Edinburgh, on the 15th of

October, 1747.

He was the eldest son of William Tytler, esquire of Woodhouselee, by his wife,

Anne Craig. The earlier rudiments of education he received from his father at

home; but in the eighth year of his age, he was sent to the High School, then

under the direction of Mr Mathison. At this seminary, young Tytler remained for

five years, distinguishing himself at once by the lively frankness of his

manners, and by the industry and ability with which he applied himself to, and

pursued his studies. The latter procured him the highest honours of the academy;

and, finally, in the last year of his course, obtained for him the dignity of

dux of the rector’s class.

On the

completion of his curriculum at the High School his father sent him to an

academy at Kensington, for the still further improvement of his classical

attainments. This academy was then under the care of Mr Elphinston, a man of

great learning and singular worth, who speedily formed a strong attachment to

his pupil, arising from the pleasing urbanity of his manners, and the zeal and

devotion with which he applied himself to the acquisition of classical learning.

When Mr Tytler set out for Kensington, which was in 1763, in the sixteenth year

of his age, he went with the determination of returning an accomplished scholar;

and steadily acting up to this determination, he attained the end to which it

was directed. At Kensington, he soon distinguished himself by his application

and proficiency, particularly in Latin poetry, to which he now became greatly

attached, and in which he arrived at great excellence. His master was especially

delighted with his efforts in this way, and took every opportunity, not only of

praising them himself, but of exhibiting them to all with whom he came in

contact who were capable of appreciating their merits. To his other pursuits,

while at Kensington, Mr Tytler added drawing, which soon became a favourite

amusement with him, and continued so throughout the whole of his after life. He

also began, by himself, to study Italian, and by earnest and increasing

assiduity, quickly acquired a sufficiently competent knowledge of that language,

to enable him to read it fluently, and to enjoy the beauties of the authors who

wrote in it. The diversity of Mr Tytler’s pursuits extended yet further. He

acquired, while at Kensington, a taste for natural history, in the study of

which he was greatly assisted by Dr Russel, an intimate friend of his father,

who then lived in his neighbourhood.

In 1765, Mr

Tytler returned to Edinburgh, after an absence of two years, which he always

reckoned amongst the happiest and best spent of his life. On his return to his

native city, his studies naturally assumed a more direct relation to the

profession for which he was destined,—the law. With this object chiefly in view,

he entered the university, where he began the study of civil law, under Dr Dick;

and afterwards that of municipal law, under Mr Wallace. He also studied logic,

under Dr Stevenson; rhetoric and belles lettres, under Dr Blair; and moral

science, under Dr Fergusson. Mr Tytler, however, did not, by any means, devote

his attention exclusively to these preparatory professional studies. He reserved

a portion for those that belong to general knowledge. From these he selected

natural philosophy and chemistry, and attended a course of each.

It will be

seen, from the learned and eminent names enumerated above, that Mr Tytler was

singularly fortunate in his teachers; and it will be seen, from those that

follow, that he was no less fortunate, at this period of his life, in his

acquaintance. Amongst these he had the happiness to reckon Henry Mackenzie, lord

Abercromby, lord Craig, Mr Playfair, Dr Gregory, and Dugald Stewart. During the

summer recesses of the university, Mr Tytler was in the habit of retiring to his

father’s residence at Woodhouselee. The time spent here, however, was not spent

in idleness. In the quiet seclusion of this delightful country residence, he

resumed, and followed out with exemplary assiduity, the literary pursuits to

which he was so devoted. He read extensively in the Roman classics, and in

French and Italian literature. He studied deeply, besides, the ancient writers

of England; and thus laid in a stock of knowledge, and acquired a delicacy of

taste, which few have ever attained. Nor in this devotion to severer study, did

he neglect those lighter accomplishments, which so elegantly relieve the

exhaustion and fatigues of mental application. He indulged his taste for drawing

and music, and always joined in the little family concerts, in which his amiable

and accomplished father took singular delight.

In 1770, Mr

Tytler was called to the bar; and in the spring of the succeeding year, he paid

a visit to Paris,

in company with Mr Kerr of Blackshiels. Shortly after this, lord Kames, with

whom he had the good fortune to become acquainted in the year 1767, and who had

perceived and appreciated his talents, having seen from time to time some of his

little literary efforts, recommended to him to write something in the way of his

profession. This recommendation, which had for its object at once the promotion

of his interests, and the acquisition of literary fame, his lordship followed

up, by proposing that Mr Tytler should write a supplementary volume to his

Dictionary of Decisions. Inspired with confidence, and flattered by the opinion

of his abilities and competency for the work, which this suggestion implied on

the part of lord Kames, Mr Tytler immediately commenced the laborious

undertaking, and in five years of almost unremitting toil, completed it. The

work, which was executed in such a manner as to call forth not only the

unqualified approbation of the eminent person who had first proposed it, but of

all who were competent to judge of its merits, was published in folio, in 1778.

Two years after this, in 1780, Mr Tytler was appointed conjunct professor of

universal history in the college

of Edinburgh with Mr Pringle; and in 1786, he became sole professor. From this

period, till the year 1800, he devoted himself exclusively to the duties of his

office; but in these his services were singularly efficient, surpassing far in

importance, and in the benefits which they conferred on the student, what any of

his predecessors had ever performed. His course of lectures was so remarkably

comprehensive, that, although they were chiefly intended, in accordance with the

object for which the class was instituted, for the benefit of those who were

intended for the law, he yet numbered amongst his students many who were not

destined for that profession. The favourable impression made by these

performances, and the popularity which they acquired for Mr Tytler, induced him,

in 1782, to publish, what he modestly entitled "Outlines" of his course of

lectures. These were so well received, that their ingenious author felt himself

called upon some time afterwards to republish them in a more extended form. This

he accordingly did, in two volumes, under the title of "Elements of General

History." The Elements were received with an increase of public favour,

proportioned to the additional value which had been imparted to the work by its

extension. It became a text book in some of the universities of Britain; and was

held in equal estimation, and similarly employed, in the universities of

America. The work has since passed through many editions. The reputation of a

man of letters, and of extensive and varied acquirements, which Mr Tytler now

deservedly enjoyed, subjected him to numerous demands for literary assistance

and advice. Amongst these, was a request from Dr Gregory, then (1788) engaged in

publishing the works of his father, Dr John Gregory, to prefix to these works an

account of the life and writings of the latter. With this request, Mr Tytler

readily complied; and he eventually discharged the trust thus confided to him,

with great fidelity and discrimination, and with the tenderest and most

affectionate regard for the memory which he was perpetuating. In 1770, Mr

Tytler was called to the bar; and in the spring of the succeeding year, he paid

a visit to Paris,

in company with Mr Kerr of Blackshiels. Shortly after this, lord Kames, with

whom he had the good fortune to become acquainted in the year 1767, and who had

perceived and appreciated his talents, having seen from time to time some of his

little literary efforts, recommended to him to write something in the way of his

profession. This recommendation, which had for its object at once the promotion

of his interests, and the acquisition of literary fame, his lordship followed

up, by proposing that Mr Tytler should write a supplementary volume to his

Dictionary of Decisions. Inspired with confidence, and flattered by the opinion

of his abilities and competency for the work, which this suggestion implied on

the part of lord Kames, Mr Tytler immediately commenced the laborious

undertaking, and in five years of almost unremitting toil, completed it. The

work, which was executed in such a manner as to call forth not only the

unqualified approbation of the eminent person who had first proposed it, but of

all who were competent to judge of its merits, was published in folio, in 1778.

Two years after this, in 1780, Mr Tytler was appointed conjunct professor of

universal history in the college

of Edinburgh with Mr Pringle; and in 1786, he became sole professor. From this

period, till the year 1800, he devoted himself exclusively to the duties of his

office; but in these his services were singularly efficient, surpassing far in

importance, and in the benefits which they conferred on the student, what any of

his predecessors had ever performed. His course of lectures was so remarkably

comprehensive, that, although they were chiefly intended, in accordance with the

object for which the class was instituted, for the benefit of those who were

intended for the law, he yet numbered amongst his students many who were not

destined for that profession. The favourable impression made by these

performances, and the popularity which they acquired for Mr Tytler, induced him,

in 1782, to publish, what he modestly entitled "Outlines" of his course of

lectures. These were so well received, that their ingenious author felt himself

called upon some time afterwards to republish them in a more extended form. This

he accordingly did, in two volumes, under the title of "Elements of General

History." The Elements were received with an increase of public favour,

proportioned to the additional value which had been imparted to the work by its

extension. It became a text book in some of the universities of Britain; and was

held in equal estimation, and similarly employed, in the universities of

America. The work has since passed through many editions. The reputation of a

man of letters, and of extensive and varied acquirements, which Mr Tytler now

deservedly enjoyed, subjected him to numerous demands for literary assistance

and advice. Amongst these, was a request from Dr Gregory, then (1788) engaged in

publishing the works of his father, Dr John Gregory, to prefix to these works an

account of the life and writings of the latter. With this request, Mr Tytler

readily complied; and he eventually discharged the trust thus confided to him,

with great fidelity and discrimination, and with the tenderest and most

affectionate regard for the memory which he was perpetuating.

Mr Tytler wrote

pretty largely, also, for the well known periodicals, the Mirror and the

Lounger. To the former of these he contributed, Nos. 17, 37, 59, and 79 ; and to

the latter, Nos. 7, 9, 24, 44, 67, 70, and 79. The first of these were written

with the avowed intention of giving a higher and sprightlier character to the

work to which they were furnished; qualities in which he thought it deficient,

although he greatly admired the talent and genius displayed in its graver

papers; but he justly conceived, that a judicious admixture of a little humour,

occasionally, would not be against its popularity. The circumstances in which

his contributions to the Lounger were composed, afford a very remarkable

instance of activity of mind and habits, of facility of expression, and felicity

of imagination. They were almost all written at inns, where he happened to be

detained for any length of time, in his occasional journeys from one place to

another. Few men would have thought of devoting such hours to any useful

purpose; but the papers of the Lounger, above enumerated, show how much may be

made of them by genius and diligence.

On the

institution of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1783, Mr Tytler became one of

its constituent members; and was soon afterwards unanimously elected one of the

secretaries of the literary class, in which capacity he drew up an account of

the Origin and History of the Society, which was prefixed to the first volume of

its Transactions. In 1788, Mr Tytler contributed to the Transactions, a

biographical sketch of Robert Dundas of Arniston, lord president of the Court of

Session; and in the year following, read a paper to the society on the vitrified

forts in the Highlands of Scotland. The principal scope of this paper, which

discovers great antiquarian knowledge and research, is to show, that, in all

probability, this remarkable characteristic of the ancient Highland forts—their

vitrification—was imparted to them, not during their erection, as was generally

supposed, but at their destruction, which its author reasonably presumes, would

be, in most, if not all cases, effected by fire. With the exception of some

trifling differences of opinion in one or two points of minor importance, Mr

Tytler’s essay met with the warm and unanimous approbation of the most eminent

antiquarians of the day.

The next

publication of this versatile and ingenious writer, was, an "Essay on the

Principles of Translation," published, anonymously, in 1790. By one of those

singular coincidences, which are not of unfrequent occurrence in the literary

world, it happened that Dr Campbell, principal of the Marischal college, Aberdeen,

had, but a short while before, published a work, entitled "Translations of the

Gospel; to which was prefixed a Preliminary Dissertation on the Principles of

Taste." Between many of the sentiments expressed in this dissertation, and those

promulgated in Mr Tytler’s essay, there was a resemblance so strong and close,

that Dr Campbell, on perusing the latter, immediately conceived that the

anonymous author had pillaged his dissertation; and instantly wrote to Mr Creech

of Edinburgh, his publisher, intimating his suspicions. Mr Tytler, however, now

came forward, acknowledged himself to be the author of the suspected essay, and,

in a correspondence which he opened with Dr Campbell, not only convinced him

that the similarity of sentiment which appeared in their respective

publications, was the result of mere accident, but succeeded in obtaining the

esteem and warmest friendship of his learned correspondent.

Mr Tytler’s

essay attained a rapid and extraordinary celebrity. Complimentary letters flowed

in upon its author from many of the most eminent men in England; and the book

itself speedily came to be considered a standard work in English criticism. Mr

Tytler had now attained nearly the highest pinnacle of literary repute. His name

was widely known, and was in every case associated with esteem for his worth,

and admiration of his talents. It is no matter for wonder then, that such a man

should have attracted the notice of those in power, nor that they should have

thought it would reflect credit on themselves, to promote his interests.

In 1790, Mr

Tytler, through the influence of lord Melville, was appointed to the high

dignity of judge-advocate of Scotland. The duties of this important office had

always been, previously to Mr Tytler’s nomination, discharged by deputy; but

neither the activity of his body and mind, nor the strong sense of the duty he

owed to the public, would permit him to have recourse to such a subterfuge. He

resolved to discharge the duties now imposed upon him in person, and continued

to do so, attending himself on every trial, so long as he held the appointment.

He also drew up, while acting as judge-advocate, a treatise on Martial Law,

which has been found of great utility. Of the zeal with which Mr Tytler

discharged the duties of his office, and of the anxiety and impartiality with

which he watched over and directed the course of justice, a remarkable instance

is afforded in the case of a court-martial, which was held at Ayr.

Mr Tytler thought the sentence of that court unjust; and under this impression,

which was well founded, immediately represented the matter to Sir Charles

Morgan, judge-advocate general of England, and

prayed for a reversion of the sentence. Sir Charles cordially concurred in

opinion with Mr Tytler regarding the decision of the court-martial, and

immediately procured the desired reversion. In the fulness of his feelings, the

feelings of a generous and upright mind, Mr Tytler recorded his satisfaction

with the event, on the back of the letter which announced it. In 1790, Mr

Tytler, through the influence of lord Melville, was appointed to the high

dignity of judge-advocate of Scotland. The duties of this important office had

always been, previously to Mr Tytler’s nomination, discharged by deputy; but

neither the activity of his body and mind, nor the strong sense of the duty he

owed to the public, would permit him to have recourse to such a subterfuge. He

resolved to discharge the duties now imposed upon him in person, and continued

to do so, attending himself on every trial, so long as he held the appointment.

He also drew up, while acting as judge-advocate, a treatise on Martial Law,

which has been found of great utility. Of the zeal with which Mr Tytler

discharged the duties of his office, and of the anxiety and impartiality with

which he watched over and directed the course of justice, a remarkable instance

is afforded in the case of a court-martial, which was held at Ayr.

Mr Tytler thought the sentence of that court unjust; and under this impression,

which was well founded, immediately represented the matter to Sir Charles

Morgan, judge-advocate general of England, and

prayed for a reversion of the sentence. Sir Charles cordially concurred in

opinion with Mr Tytler regarding the decision of the court-martial, and

immediately procured the desired reversion. In the fulness of his feelings, the

feelings of a generous and upright mind, Mr Tytler recorded his satisfaction

with the event, on the back of the letter which announced it.

In the year

1792, Mr Tytler lost his father, and by his death succeeded to the estate of

Woodhouselee, and shortly after Mrs Tytler succeeded in a similar manner to the

estate of Balmain in Inverness-shire. On taking possession of Woodhouselee, Mr

Tytler designed, and erected a little monument to the memory of his father, on

which was an appropriate Latin inscription, in a part of the grounds which his

parents had delighted to frequent.

This tribute of

filial affection paid, Mr Tytler, now in possession of affluence, and every

other blessing on which human felicity depends, began to realize certain

projects for the improvement and embellishment of his estate, which he had long

fondly entertained, and thinking with Pope that "to enjoy, is to obey," he

prepared to make the proper use of the wealth which had been apportioned to him.

This was in opening up sources of rational and innocent enjoyment for himself,

and in promoting the happiness and comfort of those around him. From this period

he resided constantly at Woodhouselee, the mansion-house of which he enlarged in

order that he might enlarge the bounds of his hospitality. The felicity,

however, which he now enjoyed, and for which, perhaps, no man was ever more

sincerely or piously grateful, was destined soon to meet with a serious

interruption. In three years after his accession to his paternal estate, viz, in

1795, Mr Tytler was seized with a dangerous and long protracted fever,

accompanied by delirium. The skill and assiduity of his friend Dr Gregory,

averted any fatal consequences from the fever, but during the paroxysms of the

disease he had burst a blood vessel, an accident which rendered his entire

recovery at first doubtful, and afterwards exceedingly tardy. During the hours

of convalescence which succeeded his illness on this occasion, Mr Tytler

employed himself in improving, and adapting to the advanced state of knowledge,

Derham’s Physico-Theology, a work which he had always held in high estimation.

To this new edition of Derham’s work, which he published in 1799, he prefixed a

"Dissertation on Final Causes." In the same year Mr Tytler wrote a pamphlet

entitled, "Ireland profiting by Example, or the Question considered, Whether

Scotland has gained or lost by the Union." He was induced to this undertaking by

the circumstance of the question having been then furiously agitated, whether

any benefit had arisen, or was likely to arise from the Union with Ireland. Of

Mr Tytler’s pamphlet the interest was so great that no less than 3000 copies

were sold on the day of publication.

The well earned

reputation of Mr Tytler still kept him in the public eye, and in the way of

preferment. In 1801, a vacancy having occurred in the bench of the court of

Session by the death of lord Stonefield, the subject of this memoir was

appointed, through the influence of lord Melville, to succeed him, and took his

seat, on the 2nd of

February, 1802,

as lord Woodhouselee. His lordship now devoted himself to the duties of his

office with the same zeal and assiduity which had distinguished his proceedings

as judge-advocate. While the courts were sitting, he resided in town, and

appropriated every hour to the business allotted to him; but during the summer

recess, he retired to his country-seat, and there devoted himself with similar

assiduity to literary pursuits. At this period his lordship contemplated several

literary works; the gratitude, and a warm and affectionate regard for the memory

of his early patron induced him to abandon them all, in order to write the Life

of Lord Kames. This work, which occupied him, interveniently, for four years,

was published in 2 volumes, quarto, in 1807, with the title of "Memoirs of the

Life and Writings of Henry Home, lord Kames." Besides a luminous account of its

proper subject, and of all his writings, it contains a vast fund of literary

anecdote, many notices of eminent persons, of whom there was hardly any other

commemoration.

On the

elevation of lord justice clerk Hope to the president’s chair in 1811, lord

Woodhouselee was appointed to the Justiciary bench, and with this appointment

terminated his professional advancement. His lordship still continued to devote

his leisure hours to literary pursuits, but these were now exclusively confined

to the revision of his Lectures upon History. In this task, however, he laboured

with unwearied assiduity, adding to them the fresh matter with which subsequent

study and experience had supplied him, and improving them where an increased

refinement in taste showed him they were defective.

In 1812, lord

Woodhouselee succeeded to some property bequeathed him by his friend and

relation, Sir James Craig, Governor of Canada. On this occasion a journey to

London was necessary, and his lordship accordingly proceeded thither. Amongst

the other duties which devolved upon him there, as nearest relative of the

deceased knight, was that of returning to the sovereign the insignia of the

order of the Bath with which Sir James had been invested. In the discharge of

this duty his lordship had an interview with the Prince Regent, who received him

with marked cordiality, and, from the conversation which afterwards followed,

became so favourably impressed regarding him, that he caused an intimation to be

conveyed to him soon after, that the dignity of baronet would be conferred upon

him if he chose it. This honour, however, his lordship modestly declined.

On his return

from London, his lordship, who was now in the sixty-fifth year of his age, was

attacked with his old complaint, and so seriously, that he was advised, and

prevailed upon to remove from Woodhouselee to Edinburgh for the benefit of the

medical skill which the city afforded. No human aid, however, could now avail

him. His complaint daily gained ground in despite of every effort to arrest its

progress. Feeling that he had not long to live, although perhaps, not aware that

the period was to be so brief, he desired his coachman to drive him out on the

road in the direction of Woodhouselee, the scene of the greater portion of the

happiness which he had enjoyed through life, that he might obtain a last sight

of his beloved retreat.

On coming

within view of the well-known grounds his eyes beamed with a momentary feeling

of delight. He returned home, ascended the stairs which led to his study with

unwonted vigour, gained the apartment, sank on the floor, and expired without a

groan. Lord

Woodhouselee died on the 5th January, 1813, in the 66th year of his age; leaving

a name which will not soon be forgotten, and a reputation for taste, talent, and

personal worth, which will not often be surpassed.

Patrick

Fraser Tytler Patrick

Fraser Tytler, the son of

Lord Woodhouselee, he was born in

Edinburgh, where he attended the

Royal High School. He was called to the bar

in 1813; in 1816 he became

King's counsel in the Exchequer, and

practised as an advocate until 1832. He moved to

London, and it was largely owing to his efforts

that a scheme for publishing state papers was

carried out. Tytler was one of the founders of

the

Bannatyne Club and of the

English Historical Society. He died at

Great Malvern on 14 December 1849. His life

(1859) was written by his friend

John William Burgon. Tytler married

Anastasia Jessey, daughter of Thomson Bonar,

Esq., (1780–1828) of Campden, Kent, by his

spouse Anastasia Jessey, daughter of Matthew

Guthrie of Halkerton, M.D.

Tytler is most noted for his

literary output. He contributed

to Allison's Travels in

France (1815); his first

independent essays were papers

in

Blackwood's Magazine.

His great work, the History

of Scotland (1828–1843)

covered the period between 1249

and 1603.

His other works include:

- contributions to

Thomson's Select Melodies

of Scotland (1824)

- Life of James

Crichton of Cluny, commonly

called the Admirable

Crichton (1819; 2nd ed.,

1823)

- a Memoir of Sir

Thomas Craig of Riccarton

(1823)

- an Essay on the

Revival of Greek Literature

in Italy, and a Life of John

Wickliff, published

anonymously (1826)

- Lives of Scottish

Worthies, for Murray's

Family Library (1831–1833)

- Historical View of

the Progress of Discovery in

America (1832)

- Life of Sir Walter

Raleigh (1833)

- Life of Henry VIII.

(1837)

- England under the

Reigns of Edward VI. and

Mary, from original

letters (1839)

- Notes on the Darnley

Jewel (1843)

- Portraits of Mary

Queen of Scots (1845).

Robert

Christopher Tytler

(1818-1872) was born in India, the son of a surgeon in the Bengal Army who had

married the daughter of a German count. Tytler joined the Bengal Army and gained

a medal for his conduct in Afghanistan in 1842. He was deeply involved in

fighting the Indian Mutiny, taking an important role in the Siege of Delhi. He

was the officer in charge of the Royal Palace at the Red Fort after it was

captured in September 1857, and although not taking part in the widespread

unofficial looting by the British, was able to pick up some incredible bargains

when the official 'Prizes of War' were auctioned.

His second wife,

Harriet Tytler,

(1827-1907), was the redoubtable daughter of another military family who later

founded the Asiatic Christian Orphanage at Simla. They were married in Lucknow

in 1848, She was the only Englishwoman present at the siege, because she could

not join the others in their retreat on elephant because of the advanced stage

of her pregnancy. Their seventh child (one of the previous six had died very

young) was born during the siege on 21 June 1857; they named him Stanley

Delhi-Force Tytler. Her remarkable memoirs of the period 1828-58 were first

published in 'Chambers Journal' in 1931, coming out later as a book from Oxford

University press (edited by Anthony Sattin) in 1986, under the title 'An

Englishwoman in India'.

After the war,

Robert Tytler was promoted to Major, and given six months leave in 1858. The

couple learnt photography from Felice Beato and John Murray before travelling

around the country taking over 500 large calotypes of scenes connected with the

Mutiny.

These images were shown to the

public by the

Photographic Society of Bengal

in 1859, and they were also on show (and for sale) at the Tytler's home in

Calcutta. The couple went back for an extended leave in England in 1860-61 and

showed the work there. Roughly 80 of their pictures are in the India Office

collection, listed as by Tytler, Robert and Harriet.

Harriet's contribution to the

pictures has not always been noted, and they are sometimes attributed to Robert

alone, but the opposite has also occured. The picture 'The

Kootub, Delhi',

included in 'India through the Lens: Photography 1840-1911' (see box, top

right), is attributed to Harriet Tytler alone. It is unclear what the basis is

for this assertion.

The

Qutb Minar

is an ornate

thirteenth-century sandstone minaret 238 ft high, built to symbolise the power

of the Islamic presence in India. The Tytler's picture is a fine two part

vertical panorama of two albumen prints, each 51.8x40cm (20x16") which join

almost perfectly. To describe it - as one reviewer did ' as 'cobbled together' -

is an insult to a fine piece of craftsmanship.

Robert Tytler

was later made Superintendent of the convict settlement at Port Blair in the

Andaman Islands from 1862-1864, probably in recognition for having sold the

crown of Bahadur Shah, the last Mughal Emperor, rather cheaply to Queen

Victoria. He did not last long in this post, as he made a disastrous error of

judgement investigating the alleged murder of some sailors by two Andamese

natives. Tytler took no notice of their evidence, regarding the natives as

unreliable. Eventually this resulted in him being retired from active duty and

put in charge of the museum at Simla until his death in 1872. The Tytlers do not

appear to have made any significant photographs after their 1858 pictures.

|

|

Patrick

Fraser Tytler, the son of

Lord Woodhouselee, he was born in

Edinburgh, where he attended the

Royal High School. He was called to the bar

in 1813; in 1816 he became

King's counsel in the Exchequer, and

practised as an advocate until 1832. He moved to

London, and it was largely owing to his efforts

that a scheme for publishing state papers was

carried out. Tytler was one of the founders of

the

Bannatyne Club and of the

English Historical Society. He died at

Great Malvern on 14 December 1849. His life

(1859) was written by his friend

John William Burgon.

Patrick

Fraser Tytler, the son of

Lord Woodhouselee, he was born in

Edinburgh, where he attended the

Royal High School. He was called to the bar

in 1813; in 1816 he became

King's counsel in the Exchequer, and

practised as an advocate until 1832. He moved to

London, and it was largely owing to his efforts

that a scheme for publishing state papers was

carried out. Tytler was one of the founders of

the

Bannatyne Club and of the

English Historical Society. He died at

Great Malvern on 14 December 1849. His life

(1859) was written by his friend

John William Burgon.

The surname of a family distinguished

in law and in the

literature of

The surname of a family distinguished

in law and in the

literature of

In 1770, Mr

Tytler was called to the bar; and in the spring of the succeeding year, he paid

a visit to Paris,

in company with Mr Kerr of Blackshiels. Shortly after this, lord Kames, with

whom he had the good fortune to become acquainted in the year 1767, and who had

perceived and appreciated his talents, having seen from time to time some of his

little literary efforts, recommended to him to write something in the way of his

profession. This recommendation, which had for its object at once the promotion

of his interests, and the acquisition of literary fame, his lordship followed

up, by proposing that Mr Tytler should write a supplementary volume to his

Dictionary of Decisions. Inspired with confidence, and flattered by the opinion

of his abilities and competency for the work, which this suggestion implied on

the part of lord Kames, Mr Tytler immediately commenced the laborious

undertaking, and in five years of almost unremitting toil, completed it. The

work, which was executed in such a manner as to call forth not only the

unqualified approbation of the eminent person who had first proposed it, but of

all who were competent to judge of its merits, was published in folio, in 1778.

Two years after this, in 1780, Mr Tytler was appointed conjunct professor of

universal history in the college

of Edinburgh with Mr Pringle; and in 1786, he became sole professor. From this

period, till the year 1800, he devoted himself exclusively to the duties of his

office; but in these his services were singularly efficient, surpassing far in

importance, and in the benefits which they conferred on the student, what any of

his predecessors had ever performed. His course of lectures was so remarkably

comprehensive, that, although they were chiefly intended, in accordance with the

object for which the class was instituted, for the benefit of those who were

intended for the law, he yet numbered amongst his students many who were not

destined for that profession. The favourable impression made by these

performances, and the popularity which they acquired for Mr Tytler, induced him,

in 1782, to publish, what he modestly entitled "Outlines" of his course of

lectures. These were so well received, that their ingenious author felt himself

called upon some time afterwards to republish them in a more extended form. This

he accordingly did, in two volumes, under the title of "Elements of General

History." The Elements were received with an increase of public favour,

proportioned to the additional value which had been imparted to the work by its

extension. It became a text book in some of the universities of Britain; and was

held in equal estimation, and similarly employed, in the universities of

America. The work has since passed through many editions. The reputation of a

man of letters, and of extensive and varied acquirements, which Mr Tytler now

deservedly enjoyed, subjected him to numerous demands for literary assistance

and advice. Amongst these, was a request from Dr Gregory, then (1788) engaged in

publishing the works of his father, Dr John Gregory, to prefix to these works an

account of the life and writings of the latter. With this request, Mr Tytler

readily complied; and he eventually discharged the trust thus confided to him,

with great fidelity and discrimination, and with the tenderest and most

affectionate regard for the memory which he was perpetuating.

In 1770, Mr

Tytler was called to the bar; and in the spring of the succeeding year, he paid

a visit to Paris,

in company with Mr Kerr of Blackshiels. Shortly after this, lord Kames, with

whom he had the good fortune to become acquainted in the year 1767, and who had

perceived and appreciated his talents, having seen from time to time some of his

little literary efforts, recommended to him to write something in the way of his

profession. This recommendation, which had for its object at once the promotion

of his interests, and the acquisition of literary fame, his lordship followed

up, by proposing that Mr Tytler should write a supplementary volume to his

Dictionary of Decisions. Inspired with confidence, and flattered by the opinion

of his abilities and competency for the work, which this suggestion implied on

the part of lord Kames, Mr Tytler immediately commenced the laborious

undertaking, and in five years of almost unremitting toil, completed it. The

work, which was executed in such a manner as to call forth not only the

unqualified approbation of the eminent person who had first proposed it, but of

all who were competent to judge of its merits, was published in folio, in 1778.

Two years after this, in 1780, Mr Tytler was appointed conjunct professor of

universal history in the college

of Edinburgh with Mr Pringle; and in 1786, he became sole professor. From this

period, till the year 1800, he devoted himself exclusively to the duties of his

office; but in these his services were singularly efficient, surpassing far in

importance, and in the benefits which they conferred on the student, what any of

his predecessors had ever performed. His course of lectures was so remarkably

comprehensive, that, although they were chiefly intended, in accordance with the

object for which the class was instituted, for the benefit of those who were

intended for the law, he yet numbered amongst his students many who were not

destined for that profession. The favourable impression made by these

performances, and the popularity which they acquired for Mr Tytler, induced him,

in 1782, to publish, what he modestly entitled "Outlines" of his course of

lectures. These were so well received, that their ingenious author felt himself

called upon some time afterwards to republish them in a more extended form. This

he accordingly did, in two volumes, under the title of "Elements of General

History." The Elements were received with an increase of public favour,

proportioned to the additional value which had been imparted to the work by its

extension. It became a text book in some of the universities of Britain; and was

held in equal estimation, and similarly employed, in the universities of

America. The work has since passed through many editions. The reputation of a

man of letters, and of extensive and varied acquirements, which Mr Tytler now

deservedly enjoyed, subjected him to numerous demands for literary assistance

and advice. Amongst these, was a request from Dr Gregory, then (1788) engaged in

publishing the works of his father, Dr John Gregory, to prefix to these works an

account of the life and writings of the latter. With this request, Mr Tytler

readily complied; and he eventually discharged the trust thus confided to him,

with great fidelity and discrimination, and with the tenderest and most

affectionate regard for the memory which he was perpetuating. In 1790, Mr

Tytler, through the influence of lord Melville, was appointed to the high

dignity of judge-advocate of Scotland. The duties of this important office had

always been, previously to Mr Tytler’s nomination, discharged by deputy; but

neither the activity of his body and mind, nor the strong sense of the duty he

owed to the public, would permit him to have recourse to such a subterfuge. He

resolved to discharge the duties now imposed upon him in person, and continued

to do so, attending himself on every trial, so long as he held the appointment.

He also drew up, while acting as judge-advocate, a treatise on Martial Law,

which has been found of great utility. Of the zeal with which Mr Tytler

discharged the duties of his office, and of the anxiety and impartiality with

which he watched over and directed the course of justice, a remarkable instance

is afforded in the case of a court-martial, which was held at Ayr.

Mr Tytler thought the sentence of that court unjust; and under this impression,

which was well founded, immediately represented the matter to Sir Charles

Morgan, judge-advocate general of England, and

prayed for a reversion of the sentence. Sir Charles cordially concurred in

opinion with Mr Tytler regarding the decision of the court-martial, and

immediately procured the desired reversion. In the fulness of his feelings, the

feelings of a generous and upright mind, Mr Tytler recorded his satisfaction

with the event, on the back of the letter which announced it.

In 1790, Mr

Tytler, through the influence of lord Melville, was appointed to the high

dignity of judge-advocate of Scotland. The duties of this important office had

always been, previously to Mr Tytler’s nomination, discharged by deputy; but

neither the activity of his body and mind, nor the strong sense of the duty he

owed to the public, would permit him to have recourse to such a subterfuge. He

resolved to discharge the duties now imposed upon him in person, and continued

to do so, attending himself on every trial, so long as he held the appointment.

He also drew up, while acting as judge-advocate, a treatise on Martial Law,

which has been found of great utility. Of the zeal with which Mr Tytler

discharged the duties of his office, and of the anxiety and impartiality with

which he watched over and directed the course of justice, a remarkable instance

is afforded in the case of a court-martial, which was held at Ayr.

Mr Tytler thought the sentence of that court unjust; and under this impression,

which was well founded, immediately represented the matter to Sir Charles

Morgan, judge-advocate general of England, and

prayed for a reversion of the sentence. Sir Charles cordially concurred in

opinion with Mr Tytler regarding the decision of the court-martial, and

immediately procured the desired reversion. In the fulness of his feelings, the

feelings of a generous and upright mind, Mr Tytler recorded his satisfaction

with the event, on the back of the letter which announced it.