Mary Seton (1541-1615) was the daughter of George Seton, 6th Lord Seton, from his second wife, Marie Pyeris (a French-born woman of Rank, and Lady in Waiting to Marie de Guise, Queen Consort of King James V of Scotland), which marriage was something unusual in the Scots society at the time.

Raised a devote Catholic, as a child, she was very tall and stately and was always called by the others by her surname of Seton. At the young ageof seven, she became a Lady in Waiting to the future Queen Mary Stuart (or "Mary, Queen of Scots), along with three other girls of similar age and of a similar standing in Scots society and they were known as the "Four Maries": Mary Seton, Mary Beaton, Mary Fleming, Mary Livingston.

The "Ballad of the Four Maries" is not actually factual, where there was no Carmichael nor Hamilton, and refers to a Mary Hamilton of another age:

"Last night there were four Marys;

Tonight there'll be but three:

There was Mary Seton and Mary Beaton,

Mary Carmichael and Me."

Following the negotiations between the Scottish and French Parliaments, which included Mary Seton's older brother George, Lord Seton, the "Four Mary's" accompanied Queen Mary to France; who would later be wed the Dauphin. They were chosen, with the exception of Mary Fleming (who was a first cousin of Mary Stuart), primarily for their Franco-Scottish parentage and family relation, and were brought up at the court of King Henry II of France and his Queen Catherine de Médicis. Mary Seton, being about a year older than her mistress, was educated along with Queen Mary prior to the marriage of her Queen to Francis, later King Francis II of France, and with whom she returned to Scotland in 1561 following Francis' death.

When Queen Mary returned to Scotland, after her ceremonial entry at Edinburgh in September 1561, she went to Linlithgow Palace, while the four Marys, accompanied by the Queen's uncle, the Grand Prior of Malta, François de Lorraine, travelled west to Coldingham Priory and Dunbar. They stopped at the house of Mary Seton's brother, George Seton, 7th Lord Seton, at Seton Palace, for dinner. The Grand Prior then returned home through England making strategic plans for Berwick-upon-Tweed and Newcastle-on-Tyne.

Mary Seton's handwriting, in those letters of hers which still exist in the Record Office and the British Museum, is remarkably like that of the Queen. It is a clear, round, Roman hand, easy to read, and a delightful change from the crabbed spider-like scratching German text then in common use. The only drawback to it was that, as Queen Mary herself observed, "it was easily imitated by the forger's vile art."

Much older than his little halfsister, Mary Seton regarded her older brother George, 7th Lord Seton, as the head of her house from the time that she was eight years of age, and as many years her senior, with almost filial respect in her devoted adherence to her Queen and friend, Mary had the encouragement and approval of her chief and brother; while, on the other hand, Lord Seton's untiring service and sacrifice in Mary Stuart's cause may be taken to show the example that Mary Seton emulated.

The Seton residences played a significant part in many crucial moments of Mary Stuart's reign. The Queen spent her honeymoon with Darnley at Seton; where Darnley was a cousin of Seton. Ironically, the last night of her marriage to Bothwell was spent at the Seton house. The Queen fled to Seton when Rizzio was murdered and again when Darnley was killed. It was again to Seton she fled after her escape from Lochleven. For his part in his Queen's support, Mary's brother, George, 7th Lord Seton was taken prisoner and his estates forfeit. He remained a prisoner until 1569, managing to stay in contact with the Queen and pursuing and delivering petitions on her behalf to England's Elizabeth I. He was forced to flee to France for a time where he was so destitute he was forced to drive a wagon for his livelihood. When James VI came to power, he was reinstated as Ambassador to France.

Family pride forbade Mary to give her hand: Lord Seton forbade his young half-sister from making a worse match than her elder sisters had done. Long years after when she was pressed to make an alliance with a younger son of a less noble house, (Andrew Beton, the younger brother of the Archbishop of Glasgow) she said that her relatives would never consent to her thus marrying with one who was not their equal; Mary Seton's half-sisters were respectively the Countess of Menteith, the Lively of Restalrig, Lady Ogilvy, and Lady Somerville.

Mary Seton's

grandfather inherited diminished property and estate because of

the extravagance of his father who was a Renaissance man who

dabbled in medicine, science, music, theology and astronomy. He

was an extravagant man, building large buildings, churches and

even a

great ship. Yet her grandfather did not have long to enjoy what

estates were left to him, as he died at Flodden.

Her grandmother, old Lady

Seton, a true maitresse femme

who had built a part of Seton

House anew and had dowered two of her granddaughters, and made

great presents to the two others, and had altogether shown

herself a sort of family Providence by virtue of the wealth she

had gained by her surpassing wisdom in the management of her own

dower lands and properties, was a factor of influence in Mary's

character, particularly in the face of adversity.

Mary Seton's

grandfather inherited diminished property and estate because of

the extravagance of his father who was a Renaissance man who

dabbled in medicine, science, music, theology and astronomy. He

was an extravagant man, building large buildings, churches and

even a

great ship. Yet her grandfather did not have long to enjoy what

estates were left to him, as he died at Flodden.

Her grandmother, old Lady

Seton, a true maitresse femme

who had built a part of Seton

House anew and had dowered two of her granddaughters, and made

great presents to the two others, and had altogether shown

herself a sort of family Providence by virtue of the wealth she

had gained by her surpassing wisdom in the management of her own

dower lands and properties, was a factor of influence in Mary's

character, particularly in the face of adversity.

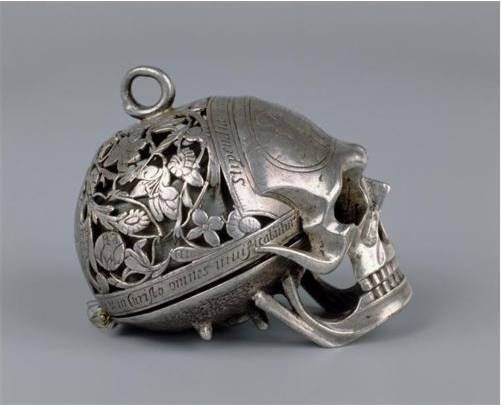

In better times, the two Mary's, the Queen and her attendant Mary Seton, were of at games of competition, one against the other. One famed match of golf at Musselburgh resulted in Mary Seton winning as a prize from her Queen, the now famed "Seton Necklace". A gift from the Queen on another occasion, resulted in the "Seton Watch": a table-clock known as a "Momento Mori"; Andrew Beton's letter writes and asks the Archbishop, with extraordinary emphasis, to see "for God's sake " that a certain drugget or hanging of silk which he had ordered for Mistress Seton was duly sent; and in another part of the same letter he returns to her interests thus :—" The watch that her Majesty ordered was for Marie de Seton ; I beg you to have it made. She wishes one like yours, with an alarm (reveil-matin) separate, which can be set when wished."

Following the events of Carberry Hill, Mary Livingstone and Mary Seton sought to shield their mistress from danger in that bitter hour. The same night, in the darkness, the Queen was carried away by armed men to imprisonment in the grim secluded castle on the isle of Lochleven; and there, soon after, her signature to her abdication was extorted by threats of immediate death. The captivity of a deposed monarch was usually, indeed, in Scotch history, the prelude to a violent death. Nevertheless, Mary Seton did not hesitate to share the gloomy and dangerous prison of her friend, at the risk of her own life. A few days after the Queen's arrival at Lochleven, Mary Seton turned from the peace and splendour of her brother's palace, and travelled to wait on her mistress in prison. At the same time Lord Seton, with his brothers-in-law Menteith, Ogilvy, and Somerville, and his cousin Tester, went to join the assemblage of the Queen's friends at Hamilton Castle, where also were found the relatives of Mary Livingstone and Mary Fleming; sure testimony to the belief in their Queen's innocence of those who knew her best.

The imprisonment of the Queen, shared voluntarily by Mary, on that dull and lonely island in Lochleven, lasted for ten months. Once in that time there was an attempt made at the Queen's escape, which failed, but which showed how much Mary Seton was prepared to risk for her mistress, and also incidentally gives the only hint that remains of the personal appearance of the young maid-of-honour:

"The Queen was of unusual height, and of a figure majestically proportioned. As Mary Seton could wear the Queen's clothes, it is obvious that she was of about the same size as her mistress. She donned the Queen's mourning robes (for though Bothwell lived, Mary always treated her marriage with him as invalid, and wore widow's mourning for Darnley to the day of her death), and thus dressed, Mary Seton placed herself with her back to the door, so that anybody peeping in might imagine they saw the Queen; while her Majesty, disguised as the castle washerwoman, was really being rowed towards the opposite shore. Brave, indeed, must Mary Seton have been to thus remain to trick the gaolers, and face their wrath when they discovered the truth. But the plot failed. The castle boatmen, piqued by the silence of the supposed washerwoman, pulled down her shawl from her head to see her face, and recognised the Queen ; and refusing to run the risk of aiding her escape, they promptly rowed her back to the castle.

The gaolers' precautions were then redoubled but nevertheless, thanks to the daring of the page Willie Douglas who boldly took the keys, muffled in a napkin, from under the very eyes of the lord of the castle as he sat at supper, the Queen and her friends, on one happy May evening, effected their escape. The party locked the great gate of the castle behind them, thus making prisoners of the gaolers. On the opposite bank of the lake, that ever-faithful friend, Lord Seton, was waiting with a troop from his personal 200 horsemen and spare horses for the ladies. The Queen and her companions instantly mounted and rode to Seton's 'shooting-box' at Niddry Castle, and thence after a brief rest, they proceeded to Hamilton Castle."

The battle of Langside scattered the Royal forces once more, and the Queen feeling her life in danger if she were taken made the unfortunate resolve to seek shelter in England, relying on Elizabeth's oft-repeated assurances of sisterly friendship. In less than a fortnight after her deliverance from Lochleven, therefore, she voluntarily placed herself, as it turned out, in an even more galling and perilous captivity in England.

At Carlisle Castle, the first residence of Mary Stuart in England, Knollys, the Vice-Chamberlain of Queen Elizabeth, waited on the Queen of Scots; and he writes to William Cecil on the 28th June 1568 a charming little detailed picture of the Queen and her devoted friend :

" Here are several gentlewomen, but none of much rank but Mistress Mary Seton, who is praised by this Queen as the finest busker (the finest dresser of a woman's hair) that is to be seen in any country ; whereof we have seen divers experiences since her coming hitherto; and among other pretty devices, yesterday and this day she did set such a curled hair upon the Queen, that was said to be a perewyke, that showed very delicately ; and every other day she hath a new device of head-dressing without any cost, and yet setting forth a woman gaily well." (original text: "Yesterday, and this daye she dyd sett sotche a curled heare uppon the Quene, that was said to be a perewyke that showed very delycately: and every other day lightly ... (word lost) she hathe a newe devyce of head dressyng, withowte any coste, and yett setteth forthe a woman gaylye well.")

Not all the record of trouble, and danger, and adventure, and devotion, can show us the sweet friendship between these two young women as does this brief picture of Mary Seton " busking " her Queen's hair and setting her rare beauty forth with ingenious devices and skilful economy, and Mary Stuart praising her highborn dresser's skill to the English gentlemen who admired its result.

Straiter and sterner grew the captivity in which the Queen of Scots was held. She was removed, in defiance of her remonstrance's, from Carlisle to Bolton, and thence to Tutbury, a wretchedly furnished house where a rampart of earth shut out the sun, and everything that was allowed to stand for a few days was found covered with mould. Thence the prison was changed to the Earl of Shrewsbury's Castle at Sheffield, where the Queen was kept for many years. In every prison, without rest or holiday, Mary Seton is found beside her friend. Lady Livingstone, the dame d'honnenr, sometimes paid a visit to Scotland, and after a few years returned to her home there. Others came and went. Mary Seton however, a prisoner of friendship, never moved from her Queen's side, and shared her confinement in unwholesome gaols, her deprivation of exercise, her lack of variety of scene and company, her hopes and fears, her worries and occupation, for months and years together they were allowed no further exercise than could be taken on the leads of the castle.

Once we find the

Queen complaining that her soiled

linen and that of her ladies was searched by men before it went

to the wash. Medicine was required for the

Queen, and her physician was

reduced to declaring that he must give up the responsibility of

his post unless the Queen of

England would let him have the necessities for his patient's

use; but the needed drugs and appliances never arrived. The

service of their own religion was interdicted to them for long

periods together. The number of the Queen's attendants was, for

a considerable period, so far reduced that her personal needs

could not be duly attended to. Yet, through confinement,

disappointment, deprivation, sickness, discomfort, insult, and

trouble, Mary Seton was always

there. They were young women of twenty-five when they entered on

their English captivity ; they lived in it together till they

were over forty years of age. All Mary

Seton's prime passed in her Queen's prisons. Life was at

stake as well as comfort and freedom sacrificed in that service.

Once we find the

Queen complaining that her soiled

linen and that of her ladies was searched by men before it went

to the wash. Medicine was required for the

Queen, and her physician was

reduced to declaring that he must give up the responsibility of

his post unless the Queen of

England would let him have the necessities for his patient's

use; but the needed drugs and appliances never arrived. The

service of their own religion was interdicted to them for long

periods together. The number of the Queen's attendants was, for

a considerable period, so far reduced that her personal needs

could not be duly attended to. Yet, through confinement,

disappointment, deprivation, sickness, discomfort, insult, and

trouble, Mary Seton was always

there. They were young women of twenty-five when they entered on

their English captivity ; they lived in it together till they

were over forty years of age. All Mary

Seton's prime passed in her Queen's prisons. Life was at

stake as well as comfort and freedom sacrificed in that service.

Yet whatever anxiety that Mary experienced, poor Andrew Beton served a long probation wishing her hand in marriage:

".. for three years later he was fain to apply to the Queen for her intercession with his obdurate lady, Mary Seton. Mary Stuart " spoke," so she declares, " three separate times " to her maid-of-honour, before she could obtain any concession for the lover who would not yield. Mary Seton pleaded the honour of her family ; the Queen promptly promised to obtain Lord Seton's consent, and to raise Andrew, whose family justified it, to nobility. Baffled on this tack, Mary announced that she had made a vow in her own mind of eternal celibacy, her desire to join a convent, which she believed she could not "honourably and conscientiously break."

The Queen, though devoutly religious, scoffed at this secret taking of the veil; she assured her friend that such a private vow was null and void, and offered to take the penalty of breaking it on to her own conscience. " At length," goes on the Queen, in the letter in which she tells this love-story to the Archbishop, "on my urgent remonstrances and persuasions, which she has considered according to her duty as the orders of an attached mistress, she has made up her mind to submit to my commands, on my assurance that I will respect her confidence and take care of her reputation. In the first place, I have resolved her from her pretended vow, which I esteem null; and if by the advice of the doctors it is found such, it will be for me to take charge of the rest.

Our young man, whom I have called into presence, has undertaken, a little rashly considering the difficulties that there are, to himself make the voyage for obtaining the resolution of the vow, and by the same journey arrange all with you. For the rest, by the first convenience you must write to her brother, to know how he will look upon what I wish, for giving all the colour necessary to the observation of the respect usual in our country where there is some difference of quality or titles. Your brother will testify what I have done in his cause, of which he shows himself not a little content and obliged by serving me, if possible, more carefully and agreeably than ever, which I take in very good part this."

Having

finished this letter to the Archbishop, the

Queen called in her friend and

read it aloud to her. Thereupon, as the

Queen tells in a postscript, Mary

Seton accused her of partiality to the lover's side. What

indulgence, she demanded, was she to receive for the long

keeping of her vow of celibacy. And, in the next place,

what credit was she to get for breaking it now at her mistress's

orders, when "she liked not what she had seen of marriage and

would rather remain in her present state". In short, she

showed herself thoroughly thorny and impracticable; and Andrew

had to start on his perilous and long voyage with no better

assurance than the bare hope that if the vow were declared void,

and if Lord Seton would give his

consent, he should be rewarded with the hand of his lady on his

return.

Having

finished this letter to the Archbishop, the

Queen called in her friend and

read it aloud to her. Thereupon, as the

Queen tells in a postscript, Mary

Seton accused her of partiality to the lover's side. What

indulgence, she demanded, was she to receive for the long

keeping of her vow of celibacy. And, in the next place,

what credit was she to get for breaking it now at her mistress's

orders, when "she liked not what she had seen of marriage and

would rather remain in her present state". In short, she

showed herself thoroughly thorny and impracticable; and Andrew

had to start on his perilous and long voyage with no better

assurance than the bare hope that if the vow were declared void,

and if Lord Seton would give his

consent, he should be rewarded with the hand of his lady on his

return.

At first Mary Seton was given a room to herself with two beds, one for her maid or 'gentlewoman' Janet Spittell. She also had a manservant called John Dumfries. In March 1569 the Earl of Shrewsbury noted that Queen Mary would sit and sew in his wife Bess of Hardwick's chamber at Tutbury Castle accompanied by Mary Seton and Lady Livingston.

While she and Queen Mary were at Tutbury Castle held by the Earl of Shrewsbury on the orders of England's Queen Elizabeth, Mary Seton's mother, Mary Pyeris, wrote a letter to Queen Mary inquiring about the health of her daughter, Mary Seton. Pyeris was soon arrested for this act, released only after the intervention of Queen Elizabeth, where in October 1570, Elizabeth heard the communique that her mother Mary Pyeris, Lady Seton, had been arrested and would be banished from Scotland for writing to her. She charitably took action and sent an advisory to the Regent Lennox that she thought it no great cause and for Pyeris to be released.

When Queen Mary was moved to Sheffield Castle in September 1571,

Mary Seton continued staying in attendance, but her own man-servant John Dumfries

was excluded and kept in the town. Her servant-woman Janet Spittle

however, was sent back

to Scotland. Mary Seton then had a remaining older woman as her servant,

although as they were soon tired of each other by April 1577, this servant

was allowed to return back to Scotland.

At Sheffield in November 1581, Robert Beale questioned her about Queen Mary's recent illness, which had a quick

onset. Seton said that she had not seen the Queen as ill before,

her side gave her evil pains especially in the thigh and leg.

The Queen lacked appetite, was losing sleep, and in Seton's

opinion could not long continue.

It is certain that her own health began to fail rapidly after that date. Yet she served her beloved friend for seven more years in captivity. However her own illnesses growing worse, her brother George 7th Lord Seton who was proceeding to France on a mission in the Queen's interests, urged his sister to travel with him to fulfill what had now become her great desire, to take the veil in the Convent of Saint Pierre in Rheims, where Queen Mary's Aunt, Renee de Guise, the Princess 'Reul', was Abbess. At the end of the year 1584, Mary now forty-two years of age and with failing health, retired to the convent in France and bade a last adieu to her friend and Monarch whom she had loved and served throughout all her life.

The tradition of the Seton ladies to retire to the service of the convent was cemented by Mary's grandmother Lady Janet Seton (nee Hepburn), the wife of George 5th Lord Seton and grand-matron of the family who had guided the affairs of the family and oversaw the rebuilding of the Collegiate Church of Seton and retired in her elder years to the 'Convent of Sciennes' in Edinburgh (The Convent of the Sister's of Saint Catherine of Sienna), which was long patronized by the Seton's from it's inception, upon her son coming of age and full-succession to the family Titles. Also following in the steps to the Convent, was Lady Katherine Seton, the great-aunt of Mary Seton.

The unabated love with which Mary Seton regarded the friend from whose side her own physical collapse had withdrawn her, is touchingly shown in a letter now existing in the Record Office. It is written by Mary from the convent of Rheims, and addressed to M. de Courcelles, the new French ambassador to Scotland ; the date is October, 1586, just the time when Babington's plot was paving the way for Queen Mary's destruction. After complimenting De Courcelles in the fashion of the time, Mary Seton goes on thus:

" It is nearly twenty years since I left Scotland, and in that time it has pleased God to take the best part of my relations, friends, and acquaintances; nevertheless, I presume there remain still some who knew me, and I shall be obliged by you remembering me to them as occasion may serve. I cannot conclude " [now the real purpose of her letter declares itself] " without adding still one word, that I am in extreme pain and distress at the news which has reached here of a fresh trouble which has fallen on the Queen my maistresse. Time does not permit me to write more. Written from Rheims with my humble recommendations, praying God, Monsieur de Courcelles, to make you more content than I now am, this 21st of October, your humble and obliged—Marie De Seton."

The latest letter extant from Mary Seton, is dated 1615—twenty-eight years after the execution of Queen Mary (in February, 1587). The (now) nun who had seen and felt so much and remained in service to the Queen and shared her captivity in England for 15 years, was at the date of her letter seventy-three years old, preceding her own death shortly afterwards. James Maitland, the son of Mary Fleming and William Maitland of Lethington, had visited her at Rheims and reported to the family that she was in great poverty and for whatever means to be made for her relief. Although any record of the response has since been lost, her will indicates that she had been relieved somewhat by family and relatives, and that in her last days had somewhat of a small wealth to bestow upon her heirs, dying in 1615 at the Convent.

Her portrait is at the Library in Paris, although damaged during the Revolution and said to be barely recognizable.

MARY

SETON

MARY

SETON