The

Flemish Origins

The

Flemish Origins

There

is no doubt that Charlemagnic blood was for some hundreds of years

after that monarch’s death the elixir of Europe. As late as the

19th century the eminent historian, Sir Francis Palgrave could

write: “Not only throughout the Middle Ages but long after that

era there was a species of mystical pre-eminence attached to the

Carlovingian lineage, which those who could claim the honour nourished, though

often in silence.”

Flanders had been founded early in the 9th century by the

semi-legendary Lideric, who came, said the early chroniclers, from

somewhere in the south of France into a land empty of everything

but forest, and cleared it. This was shortly after the death of

Charlemagne, who had of course been it’s overlord. The marriage

between Lideric’s grandson, Baldwin I, and Judith, daughter of

Charles the Bald of France, brought a respectability and a

strength to Flanders; it also put the magic Carolingian blood into

the veins of the comital house, since the bride was Charlemagne’s

great-granddaughter.

In the 9th and 10th centuries the comparative stability and

prosperity of Flanders caused a number of ancient comtes around

her perimeter to attach themselves to the new power. Among them

were Hainaut, Mons, Louvian, Alost (or Gand), and Guines. Boulogne,

with it’s own subsidiary comtes of Lens, Hesdin and St. Pol, was

also allied to Flanders, as was Ponthieu, away on the Norman

border. All were linked by close personal ties to the comital

family of the Baldwins. All regarded themselves, and were ruled in

1066 by men directly descended from Charlemagne.

Through Lothair, son of Charlemagne’s third son, Louis the Pious,

the counts of Alost trace a connection with the Holy Roman Empire;

Guines was an offshoot of this house via Theodoric, Count of Gand,

a younger son of that count of Alost who had married Lieutgarde,

daughter of Count Arnulf I of Flanders – himself a ruler who was

not only a Charlemagne descendant but had married one in Adela

(some genealogists call her Alix), daughter of Count Hubert II of

Vermandois, whose own great house descended directly from Pepin,

King of Italy, Charlemagne’s second son. The richest Carolingian

ancestry of all was that enjoyed by the Count Eustace II of

Boulogne; not only did he descend, through Ponthieu and Guines,

from Charlemagne’s favourite daughter, Berthe, and the

poet-courtier, Angilbert, who during the emporer’s lifetime had

been given west Flanders to rule over, but he was also the

great-grandson, through his mother, Maud of Louvain, of Charles,

Duke of Lorraine, the last male heir of the Carolingians.

Through all the troubled years after the death of Charlemagne,

Flanders and its subsidiary comets had managed to retain something

of his rule, keeping a living continuity with its precepts which

was in marked contrast with the rest of the Frankish empire. The

castle of the counts of Flanders at Ghent was a somber place,

desperately fortified by Lideric against the Viking invaders, and

expanded in later generations to express a somewhat brutal

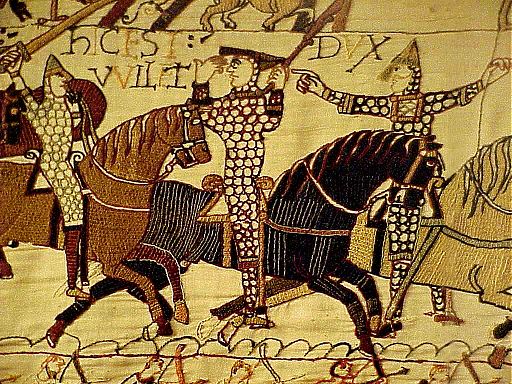

strength. His armies and those of his descendants, the Baldwins,

were stalwart, well-trained, and all but unbeatable. About the

chateau at Boulogne there was an altogether different atmosphere,

a sort of luxurious assurance, recognizable as the epitome of

aristocracy, that gave the equally efficient forces there an extra

quality of gallantry and bravura.