|

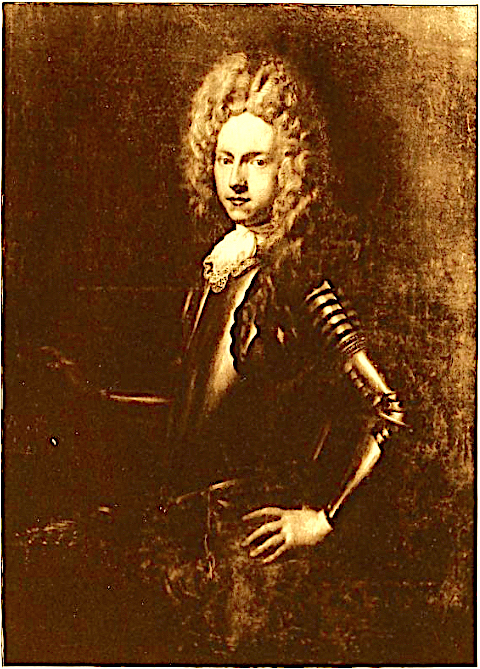

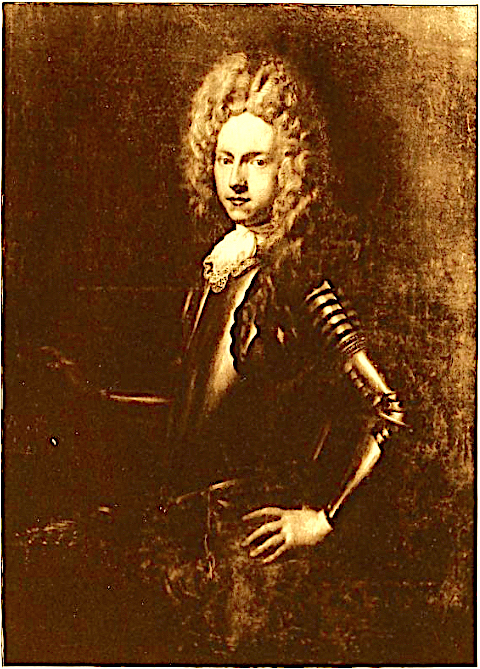

George Seton, 5th Earl of Winton

GEORGE SETON, 5th and last Earl

of Winton, was possessed

of excellent abilities, but from his early years he displayed a marked

eccentricity of character. He had travelled with his father in travels in France

and the low countries, and benefitted from a good foundation in his education.

However, some family misunderstandings caused him to leave

home while a mere youth, and he spent several years in France as bellows-blower

and assistant to a blacksmith, without holding any intercourse with his family.

On the death of his father the 4th Earl of Winton, Viscount

Kingston the next heir taking for granted that the young 5th Earl

was dead was proceeding to take possession of the title and

estates which were then also being shared by Seton of Garleton who

was also involved in the discrediting claim against the absent Earl, when suddenly the 5th Earl appeared and vindicated his

rights. It was afterwards

ascertained that a confidential servant kept him apprised of what was taking

place at home and in the family, and had sent him notice of his father’s death.

Subsequent to the

fourth Earl of Winton’s death in 1704, it had been seen that the Kingston family

were then considered, in the event of the failure of his two sons, his nearest

heirs-male. In the processes which ensued upon this account between George

the attainted Earl and the Kingston family, Archibald Viscount Kingston, was the

principal party against the latter:

Libelled Summons before the Court of Session, signeted 23rd May 1710, with

execution thereon, dated 24th May 1710, at the instance of Archibald

Viscount of Kingston, nearest and lawful appearand heir to the deceased George

Earl (fourth Earl) of Winton.

The Seton family,

as we have seen previously, had always been noted for their loyalty and their attachment to

the old Church, and the last Earl, though he had renounced the Romish faith,

held firmly to the political creed of his ancestors. In 1712 the Earl of Winton reprinted in a smaller

form the Book of Common Prayer which had been prepared for Scotland in 1637.

This book seems to have been actually used in places in the 18th century and it

exercised a wide influence.

He was living peaceably in

his own mansion at Seton when the rebellion of 1715 broke out. It is probable

that he would, under any circumstances, have taken the field in behalf of the

representative of the ancient Scottish sovereigns; but his doing so was

hastened, if not caused, by the outrageous treatment which he received from a

body of the Lothian militia, who forcibly entered and rifled his mansion at

Seton, as he alleged on his trial, ‘through private pique and revenge.’ ‘The

most sacred places,’ he adds, ‘did not escape their fury and resentment. They

broke into his chapel, defaced the monuments of his ancestors, took up the

stones of their sepulchres, thrust irons through their bodies, and treated them

in a most barbarous, inhuman, and unchristian like manner.’ On this disgraceful

outrage the Earl took up arms against the Government, assumed the command of a

troop of horse mostly composed of gentlemen belonging to East Lothian, and

joined the Northumbrian insurgents under Mr. Forster and the Earl of

Derwentwater. Their numbers were subsequently augmented by a body of Highlanders

under Brigadier Macintosh, who formed a junction with them at Kelso.

The English

insurgents insisted on carrying the war into England, where they expected to be

reinforced by the Jacobites and Roman Catholics in the northern and western

counties. The Scotsmen proposed that they should take possession of Dumfries,

Ayr, Glasgow, and other towns in the south and west of Scotland, and attack the

Duke of Argyll, who lay at Stirling, in the flank and rear, while the Earl of

Mar assailed his army in front. The English portion of the insurgent forces,

however, persisted in carrying out their absurd scheme in spite of the strenuous

opposition of the Scots, and especially of the Highlanders, who broke out in a

mutiny against the English officers.

The Earl of Wintoun disapproved so strongly

of this plan that he left the army with a considerable part of his troop, and

was marching northward when he was overtaken by a messenger from the insurgent

council, who entreated him to return. He stood for a time pensive and silent,

but at length he broke out with an exclamation characteristic of his romantic

and somewhat extravagant character. ‘It shall never be said to after generations

that the Earl of Wintoun deserted King James’s interests or his country’s good.’

Then, laying hold of his own ears, he added, ‘You, or any man, shall have

liberty to cut these out of my head if we do not all repent it.’

But though this

unfortunate young nobleman (he was only twenty-five years of age) again joined

the insurgent forces, he ceased henceforward to take any interest in their

deliberations or debates. The Rev. Robert Patten, who officiated as chaplain to

the insurgents, and afterwards wrote a history of the rebellion, indeed states

that the Earl ‘was never afterwards called to any council of war, and was

slighted in various ways, having often no quarters provided for him, and at

other times very bad ones, not fit for a nobleman of his family; yet, being in

for it, he resolved to go forward, and diverted himself with any company,

telling many pleasant stories of his travels, and his living unknown and

obscurely with a blacksmith in France, whom he served some years as a

bellows-blower and under-servant, till he was acquainted with the death of his

father, and that his tutor had given out that he was dead, upon which he

resolved to return home, and when there met with a cold reception.’

The Earl fought with

great gallantry at the barricades of Preston, but was at last obliged to

surrender along with the other insurgents, and was carried a prisoner to London,

and confined in the Tower. He was brought to trial before the House of Lords,

15th March, 1716, and defended himself with considerable ingenuity. Such was the

sensation of the Earls Trial, the local Printer of the time, Daniel Bridge, was

noted for his own trial for the printing of the Earls Trial proceedings, noted

in the House of Lords Journal, Volume 20, 27th April, 1716. The Earl fought with

great gallantry at the barricades of Preston, but was at last obliged to

surrender along with the other insurgents, and was carried a prisoner to London,

and confined in the Tower. He was brought to trial before the House of Lords,

15th March, 1716, and defended himself with considerable ingenuity. Such was the

sensation of the Earls Trial, the local Printer of the time, Daniel Bridge, was

noted for his own trial for the printing of the Earls Trial proceedings, noted

in the House of Lords Journal, Volume 20, 27th April, 1716.

The High Steward,

Lord Cooper, having overruled his objections to the indictment with some

harshness, ‘I hope,’ was the Earl’s rejoinder, ‘you will do me justice, and not

make use of "Cowper-law," as we used to say in our country—hang a man first and

then judge him.’ On the refusal of his entreaty to be heard by counsel, he

replied— ‘Since your lordship will not allow me counsel, I don’t know nothing.’

He was of course found guilty, and condemned to be beheaded on Tower Hill. ‘When

waiting his fate in the Tower,’ says Sir Walter Scott, ‘he made good use of his

mechanical skill, sawing through with great ingenuity the bars of the windows of

his prison, through which he made his escape.’

Although the

Earls of Winton and Nithsdale found means to escape out of

the Tower, and Messrs. Forster and M‘Intosh escaped from

Newgate, it was supposed that motives of mercy and

tenderness in the Prince of Wales, afterwards King George

II, favoured the escape of all these gentlemen.

After his escape, he maintained an active presence in the Scots circles in

France and Rome. Among the many interesting manuscripts preserved in the

archives of the Grand Lodge of Scotland are the Minutes of a Lodge of Scottish

Freemasons existing in Rome in the years 1735,1736 and 1737, from which we find

that the Earl of Winton was himself admitted a Mason under the name (which he

assumed on his attainder) of George Seaton Winton at a meeting held at Joseppe's,

in the Corso, Rome, on l6th August 1735.

(See Hughan's The

Jacobite Lodge at Rome.1735-7. published by the Lodge of Research.

Leicester.1910.).

Despite his

attainder, the Earl maintained active communications with

various tenants on his Estates and directed various affairs

regarding them while in exile. He continued to work to

have his Estates restored, and in 1736, in the Chronological

Table of Private and Personals Acts of the Parliament of

Great Britain, there is recorded under 10 GEO 2, c. 25, the

Act of Restitution for George Seton, Earl of Winton, his Act

submitted as follows:

Restitution of George Seton:

enabling him to sue or maintain any action despite his

attainder and to take or inherit any estate.

During his exile, he

can have had little money, but managed to carry on social

life of a sort. In 1736 his name appears in

the Minute Book of the Masonic Lodge in Rome as having

become a Mason, while the following year he was Grand

Master .

In 1740 he was in the Chevalier's Cabinet, vagrant Scots met

him occasionally and, in 1736, Sir Alexander Dick speaks of

having met him and others in a coffee house where they "fell

a singing old Scots songs and were very merry".

In September 1743 Lord Lovat wrote to Lord Grange sending

him a cypher in which Lord Winton is referred to as 'Mr.

Hepburn'.

Among the legends that float round

this interesting domain, there is one relative to George, fifth Earl of Wintoun.

Prior to departing on his ill-fated expedition, he is said to have buried a

large quantity of plate and other valuables, with the assistance of a blacksmith

in the neighbourhood, in whose fidelity he placed reliance. The recollection of

this buried treasure haunted him in his weary exile on the continent, and he

contrived to return to Scotland, in the hope of recovering what he had so

carefully deposited. The search was fruitless, and he fled in despair. It was

afterwards observed that the family of the blacksmith became opulent farmers in

East Lothian. w. c..

During this time Seton

Palace had fallen into disrepair, but it had been occupied

for some time by Elizabeth Stevenson or Pitcairn. Writing to

Alexander Hay or Drumelzier in February 1757 from France,

Sir George Seton Bt . of Garlston refers to the wrecking of

the house and its contents and says "the auld wife Pitcairn"

had pilfered many things and "furnisht an apartment in

Winton of the debris and plunder of "Seton House". At the

same time he asks Hay if nothing can be done to recover the

family pictures from Lord Somerville, "which he alwaise said

he would give up to the "family" .

The 5th Earl of winton

then, ended his motley life at Rome

in 1749, aged seventy, and with him terminated the main branch of the long and

illustrious line of the Setons. It is however, not without further

controversy, for it will be noted in the claim of the Seton's of Bellingham,

that the Earl married a lady Margaret M'KLear (McClear or McClure, daughter of a

Physician) privately in a Catholic Church in Edinburgh and had an only child and

heir, named Charles Seton who was raised by the Thompson family at Dunterly in

Bellingham. This claim was contested by the Earl of Eglinton in his

Service to claim the Winton Honours.

Male cadets of this family, however, came by

intermarriage to represent the great historic families of Huntly and Eglinton,

besides the ducal house of Gordon, now extinct, and the Earls of Sutherland,

whose heiress married the Marquis of Stafford, afterwards created Duke of

Sutherland. The earldoms of Wintoun and Dunfermline, the viscounty of Kingston,

and the other Seton titles were forfeited for the adherence of their possessors

to the Stewart dynasty, and have never been restored; but the late Earl of

Eglinton was, in 1840, served heir-male general of the family, and, in 1859, was

created Earl of Wintoun in the peerage of the United Kingdom.

Extract Registered Sasine of

the Earldom

of Winton

Dated 9th April, and recorded 5th June

1697, in the particular Register of Sasines at Edinburgh, in favour of George

Lord Seaton, afterwards fifth Earl. This sasine bears to proceed upon a

disposition by George, the fourth Earl of Winton, dated 7th April

1697, in favour (1st) of the said George Lord Setoune, who is

designed eldest lawful son of Earl George; and (2d) Christopher Seaton, second

lawful son of the said noble Earle. The sasine does not bear that the disposition

was in favour of any other party nomination, although it recites a variety of

general substitutions to heirs to be proreated of the Earl, and his above named

two sons; and, at p. 24, there is recited a provision in favour of Dame

Christian Hepburne, Countess of Wintoune, our spouse, in caise she shall happen

to survive was (the fourth Earl).

This sasine proves the two sons

of George the fourth Earl’s second marriage; and that of 7th April

1697, when the youngest sone would be fourteen years of age, he had no other

issue, male or female.

Extract Registered

Disposition and Assignation by George fourth Earl of Winton, of his general

estate, in favour of his eldest sone George Lord Seaton, dated 7th

April 1697, and recorded in the Books of Session, 27th June 1710.

In this Disposition the said

George Lord Seaton is designed, "our eldest lawful son, procreate betwixt us and

Dame Christian Hepburn, Countess of Winton, our spouse".

Bond of provision by the said

fourth Earl of Winton, in favour of Christopher Seaton, he second son dated 7th

April 1697. This bond designs the above Christopher, our second lawful son,

procreate betwixt us and Dame Christian Hepburn, Countess of Winton, our spouse.

Another Bond of Provision by

the said fourth Earl of Winton in favour of Christopher Seaton, his second son,

dated 29th May 1703. This bond also describes Christopher as our

second lawful son.

Disposition and Assignation

by the same to the same, dated 29th May 1703, of an apprising of the

lands of Carrieston, for 9000 merks. In this deed, Christopher is like wise

called the Earl’s second son.

Testament of the said George

fourth Earl, dated 21st February 1704. This testament proceeds as

follows: We nominate, constitute and ordain our well-beloved sons, George Lord

Seaton, our eldest son and apparent heir, and Mr. Christopher Seaton, his

brother-german, procreate betwixt us and our well-beloved spouse Dame Christian

Hepburn, to be our only executors, sold legatees, and universal intromitters

with our haill goods, &c.

Neither this testament, nor any of

the other deeds just described, make mention in any way of any other son or

child of the fourth Earl, other than the two sons, George Lord Seaton and

Christopher; and this, joined to the fact that the testament was executed

twenty-one years after the birth of Christopher the second and youngest son, and

as will immediately be seen, within a month of the Earl’s death, establishes

that there were no other issue of the fourth Earl.

That the said George fourth Earl

of Winton died 6th March 1704, and was succeeded by the above

mentioned George Lord Seaton, his eldest son, as fifth Earl of Winton.

In a printed condescendence

in an action between the children of James Smith (factor for the fourth Earl)

and the said George the fifth Earl, which bears date 24th January

1715, it is stated, that George the fourth Earl had died upon the day of

_________ 1704 years.

General Retour of the Service

of George fifth Earl of Winton to his father, dated 4th July 1710.

This retour designates the parties as follows: Quondam Georgius Comes de Winton

&c.

Pater Georgij nunc

Comitis de Winton, Domini Seaton et Tranent, latoris præsentium, ejus unici

legitimi filij nunc viventis procreat, inter illum et quondam Christianam

Comitissam de Winton, ejus sponosam. Obiit ad fidem et pacem S.D.N.Reginæ nune

regnantis; Et quod Dictus Georgius nunc Comes de Winton, est legitimus et

propinquior hæres masculus et lineæ dicti quondam Georgij Comitis de Winton,

ejus patris.

This service

proceeded at Edinburgh, in the Macers’ Court, under the commission issued from

Chancery, and before the following jury:

1.

James, Duke of Montrose 2.

William, Marquis of Annandale

3. John, Earl of Laudredale

4. James, Earl of Seafield

5. William. Lord Saltoun

6. _____, Lord Blantyre

7. Lord President Dalrymple of

North Berwick 8. Adam Cockburn of Ormiston,

Lord Justice-Clerk

9. Sir Robert Dundas of Arniston 10 Sir John Lauder of Fountainhall

11 Sir William Anstruther

12 Mr. James Erskine of Grange

13 Sir Gilbert Elliot of Minto

14 Mr. John Murray of Borohill

Sir Dougald Stewart of Blairhall

All Senators of the College of

Justice.

In a Printed Information,

dated 19th July 1711, in an action between George the fifth Earl and

Archibald Viscount Kingston, it is stated that the above Christopher who was the

fourth Earl’s second son, lived nine months after the Earl, (fourth Earl).

It will be proved that Christopher

himself died 5h January 1705, and therefore the fourth Earl must have died

before April 1704.

Charter of Resignation by

George fifth Earl of Winton, in favour of George Seaton of Barns, dated 31st

March, 1715. In this charter the granter is designed Georgius Comes de Winton,

Dominus Seaton et Tranent, unicus legitimus filius et hæres deservit, et

retornat, quondam nobili et potenti Comiti Georgio Comiti de Winton, nostro

patri, secundum Retornatum Nostrum o Cancellario extractum de data quarto die

mensis Julij anno 1710.

This proves that the fifth

Earl, alive in 1715, was the same Earl who was served by the retour of 1710.

The last described four

documents prove the death of George the fourth Earl, and that he was succeeded

by his eldest son George, as fifth Earl of Winton.

That George fifth Earl of Winton,

having, as has been shown, succeeded his father in 1704, was, of date 16th

and 19th

March 1716, convicted of high treason; but afterwards, on the 4th

August 1716, escaped from the Tower, and died at Rom the 30th

September 1749; and that he had no issue, having died unmarried.

In Crawford’s Peerage of Scotland, which was published in 1716, there is

no mention of the said George the fifth Earl having been previously married; and

if such had been the case, the fact must have been stated as of more consequence

than several particulars which Crawford does mention regarding his Lordship, and

in conformity with the writer’s rule in other cases where marriage had taken

place.

In Nisbet’s Heraldry, published in 1722, there is likewise the same

silence as to any marriage of the said Earl.

In the Calendar of the House of Lords in 1716 – duplicate in the

Advocates’ Library, published by authority – the proceedings on the impeachment

of this Earl are stated, abridged from the Journal of the House. In the whole

proceedings, there is no mention made of any application by wife or child for

admission to see the attainted Earl, or any reference whatever to the Earl

having any such. This is remarkable, because, during the impeachments of other

Lords before the same tribunal, and at the same period, where the party had a

wife or children, such applications and references were usual, and the

circumstances related; and they were the more to be expected in the present

instance, as the Earl sought delay, grounded upon the non-arrival of witnesses

and friends from the North.

Factory, dated 21st, and Recorded in the Books of Council and

Session the 27th January 1716, by George Earle of Wintoune, Lord

Seton, Baron of Tranent, in favour of Elizabeth Stevenson, relict of Archibald

Pitcairn of that ilk, Doctor of Medicine, which narrates that Forsameikle as our

present circumstances does not allow us to be in Scotland for managing our

affairs, &c, and contains no reference to family or marriage. The testing

clause is as follows: In witness whereof, written by Charles Menzies of

Kinmundie in Scotland, we have subscribed thir presents, at and within the Tower

of London, ye 21st day of January, 1716 years, &c.

This corroborates the other proof that

the fifth Earl was not married.

In Patten’s History of the Rebellion, printed at London, 1717, (p. 130)

it is stated that George Seaton, Earl of Winton, made his escape out of the

Tower, August 4th, 1716.

In the Caledonian Mercury, No. 4567, 16th January 1750, the

attainted Earl’s death is announced as follows: Letters from Rome bring advice

that the Earl of Winton, who was condemned to die in 1715, but escaped from the

Tower, died there the 30th of September last, N.S., aged upwards of

70, and was buried in the place set apart for the Protestants.

The fact of the attained Earl

having gone to Rome after his escape from the Tower, is established by Lord

Orford, who, in speaking of the Pretender, mentions Lord Winton when he (Lord

Orford) was at Rome, as forming one of the Pretender’s slender Cabinet.

In Edinburgh Magazine for 1750, the attainted Earl’s death is likewise

announced as follows: December 19, 1749. At Rome, aged above 70, George Earl

of Winton. His Lordship was engaged in the Rebellion 1715, and surrendered at

Preston in Lancashire, on the 14th November that year, with several

Scots and English Lords, &c, to the Generals Carpenter and Wills. He was

brought to London, December 9th and on the 10th of January

following, was impeached by the Commons of high treason. On the 19th,

the date appointed for the trial, he pled no guilty, and his trial was put off

from time to time, till the 15th of March when he was brought, and

received sentence of death on the 19th; but he escaped from the Tower

soon afterwards, and had lived in foreign parts ever since. In Edinburgh Magazine for 1750, the attainted Earl’s death is likewise

announced as follows: December 19, 1749. At Rome, aged above 70, George Earl

of Winton. His Lordship was engaged in the Rebellion 1715, and surrendered at

Preston in Lancashire, on the 14th November that year, with several

Scots and English Lords, &c, to the Generals Carpenter and Wills. He was

brought to London, December 9th and on the 10th of January

following, was impeached by the Commons of high treason. On the 19th,

the date appointed for the trial, he pled no guilty, and his trial was put off

from time to time, till the 15th of March when he was brought, and

received sentence of death on the 19th; but he escaped from the Tower

soon afterwards, and had lived in foreign parts ever since.

It is to be presumed, that in

giving such accounts of the attainted Earl as the above, if he had left lawful

issue, or had been married, the facts would naturally have been stated. In the London Magazine, January 1750, the attainted Earl’s death is

announced as follows: The late Earl of Winton, at Rome, on December 30th.

He was condemned to die for the Rebellion of 1715; but escaped out of the Tower.

In Sir Robert Douglas’s Peerage of Scotland, published in 1764, it is

expressly stated, that the attainted Earl died at Rome, anno 1749, and having no

issue, in his ended the male line of George Lord Seaton, eldest son of George

second Earl of Winton, and that the male line of Alexander Viscount Kingston,

his (George third Earl’s) second son having also failed, the representation of

this noble family devolved upon the descendants of Sir John, his (third Earl’s)

third son, (Sir John Seaton of Garleton).

N.B. The second Earl in the above

passage should be third; -- the slight numerical difference arising from the

circumstances of the second Earl’s Resignation, as already detailed under Branch

1. p. 4.

This statement was made by

Douglas only fifteen years subsequent to the attainted Earl’s death, when the

facts must have been well known. The Record by Sir Robert Douglas in all that

relates to the Winton family, rests upon far higher and more direct authority

than is usually the case with similar works, as is established by the evidence

which he gave as a witness, and one of the inquest in the service to be

immediately referred to, of Mrs. Mary Seaton or Arrat, youngest daughter of Sir

George Seaton second of Garleton, to her eldest brother Sir George Seaton in

1769, being five years after he published his work. In that service he not only

deponed to the propinquity, and that the genealogy mentioned in the brieve and

claim is true and authentic. But Sir Robert gives as his cause scientia that he

had in his hands the whole papers of the family of Winton when he wrote his book

of the Peerage of Scotland, and examined these; which book he produces to the

Jury.

It should be noted that in the

Records of the Mason's Lodge in Rome, where George, 5th Earl was a member, it

states that the records of the Lodge there were kept by George Seton Winton (his

name in exile), Earl of Winton, and preserved and passed on by his widow

(c.1799). There is then, evidence to suggest that the 5th Earl of Winton

was indeed married, and likely his second marriage.

Note also: In the in the Chronological

Table of the Private and Personal Acts of the Parliament of Great Britain,

Part 10 (1727-1736), Acts of the Parliaments of Great Britain, for the year

1736, C.25, Restitution of George Seton: enabling him to sue or maintain any

action despite his attainder and to take or inherit any estate. The 5th

Earl of Winton had petitioned from Rome and was given a Restitution by

Parliament.

The earl died at Rome, December 19,1749, and according to usual accounts the

Earl had never been married and the family in the direct line was extinct. An

attempt was made to set aside the accepted belief on this point within our

recollection. A young man named George Seton, who followed the profession of a

saddler, at Bellingham, in the county of Northumberland, arrived in Edinburgh in

1825, and forthwith proceeded to have himself served as heir-of-line to the noble

family of Seton.

At that time, the serving of heirs before bailies

was rather a

loose process, and led to some strange assumptions of dignity. George Seton, the

saddler from Bellingham, succeeded in a process of this nature before the bailies of Canongate. The evidence he appears to have relied on was a

traditional belief that George, fifth Earl of Wintoun, had been married, about

the year 1710, to Margaret M'Klear, daughter of a physician in Edinburgh.

Charles Seton, a son of this pair, was said to have been born in Northumberland

; as evidence of which fact there was produced 'a certificate by Mr Thomas

Gordon, minister at Bellingham, of the birth of Charles Seton, dated 11th June

1711.

The birth of Charles Seton was undeniable, but no proper proof was

advanced that he was the son of the attainted Earl of Wintoun, and growing up he

resided as a labourer at Dunterly, in the parish of Bellingham, and George, the

claimant in question was his lawful grandson. From the evidence of witnesses,

there were probable grounds for believing that George Seton was the

great-grandson of the unfortunate earl; but the want of a certificate of the

marriage with Margaret M'Klear settled the invalidity of the claim ; and it was

reduced by the Court of Session.

Later records were

found to show that the family of McKlear was

actually that of George

McLair

(also written as: McKlear, McClure),

the Physician and Portioner in Preston, and where

his father George McLair of Prestown, N. B. ,

established his claim, in May, 1664, to be son and

heir of George McLair, — as the Scotch

'Inquisitiones Generales,' abridged by Thomson,

show. George McLair had married Isobel Seton

as her second husband (she married firstly, Normand

Blackadder the Baillie of Cockenzie), eldest

daughter of Robert Seton, Baillie of Tranent and

younger son of the family of the Seton's of St.

Germains by his wife Jean Menies, and a cousin of

the Earl of Winton. Margaret McKlear was the

eldest daughter of George McLain and Isobel Seton.

Among the legends that float round this interesting domain there is one:

"relative to George, fifth Earl of Wintoun that prior to departing on his ill-fated

expedition he is said to have buried a large quantity of plate and other

valuables, with the assistance of a blacksmith that he was acquainted with in the neighbourhood

and in whose fidelity he had placed reliance. The recollection of this buried

treasure haunted him in his weary exile on the continent, and after many years

he contrived to return to Scotland in the hope of recovering what he had so

carefully deposited. Unable to locate the blacksmith, the search was fruitless

and he fled in despair. It was afterwards observed that the family of the

blacksmith became opulent farmers in East Lothian."

This particular story has

more than just a few

elements to give it credibility: in that the 5th Earl having been a blacksmith's

apprentice and bellows-blower during his time in Flanders; was later known to

have been familiar with the local tenants and tradesmen on his estate after his

return and recovery of his title; he

was given to maintaining secrets, and with the actions of Seton of Garleton and the Viscount of Kingston's attempts to seize his title and estates,

the 5th Earl was very distrustful of his extended-family; he had an alliance in

Northumberland with the Earl of Derwentwater prior

to and during the rebellion of 1715 and had

travelled to visit there on many occassions.

These combined with the growing Jacobite activites of the early 1700's leading up to the events of 1715, and the

raid upon the Earl's Palace of Seton and destruction of his Collegiate Church

that when combined is more than sufficient evidence and circumstance to warrant the

hidden cache of valuables to be placed should there be a need. Several sources also

note that the 5th Earl had later visited Scotland in disguise, giving further credence

to the Bellingham-Hancock claim that he had a son and visited him in

Northumberland, and seeked to recover a hidden fortune that had been cached for

safe-keeping.

All of the above give

enough circumstantial-evidence to warrant renewed investigation into the reality that the 5th

Earl was in fact married. And, oddly enough, from the Masonic records of

Rome there is the mention that the Masonic-records

there were passed on by the 5th Earl of Winton's

widow following his death, proving not only was he

married, but that that he was possibly married twice,

and certainly had a mistress, Elizabeth Stevenson,

who acted on his behalf while he was imprisoned in

London. While the male-line of the 5th Earl

from Margaret Mk'Clear (McLain) in fact died out, the female-line passed to that

of the Seton-Hancock family. However, he may well have had legitimate male-issue from

his second marriage, to which the Winton family who at one time resided in

Ireland during the late 1700's and early 1800's

claim descent from, and also had a son John Seton

from Elizabeth Stevenson.

Interestingly

enough, when the Eglinton-Claim was filed, the line

of the Seton's of St. Germains was ignored, and

should it have been included would have showed not

only the marriage of the daughter of Robert Seton,

Isobel to George McLair of Preston, but also of the

marriage of the Earl of Winton to the

great-granddaughter of Sir John Seton of St.

Germains, Margaret McLair/McKlear.

One of the 5th Earls friends was

Dr. Archibald Pitcairn of that ilk, an eminent Edinburgh physician, who had

married as his second wife in 1693 Elizabeth Stevenson, also a doctor. Dr.

Pitcairn died in 1713, leaving by her two sons and two daughters. One son

Archibald came out in the Rising and was captured and sentenced to death, but

was released through private interest with Walpole (afterwards Earl of Oxford).

On 16th February 1716 Elizabeth

came to the Tower and saw the Earl and brought him a sum of £1000 sterling from

his estates, she having on 27th January been appointed by him his "factrix" .

For this money he gave a receipt. 1 - On a later occasion she brought him a

further sum of £5000. This was only discovered in 1724 when she addressed the

Commissioners of Forfeited Estates, stated what she had done and told them that,

as factrix, she had recouped herself £1120, and claimed the balance of £3879 out

of the Estate.

In the very rare printed pamphlet, in which this appears, she is said to have

put forward some letters to her from a Mrs Corsbie "who was then attending the

"said Earl" in prison. This woman had an alias "Margaret McKlear" . The Earl's

solicitor Charles Menzies W.S., also deponed that this lady "by favour of the

"warders" had access to the Earl. She was in London as a witness for the Earl.

The Earl, through the activity of

Elizabeth Stevenson, had money, and the simplest explanation of his escape from

the Tower was that he had bribed his two warders and walked out. The warders

admitted that they had absented themselves, contrary to orders. It is at least

unnecessary to accept the statement of Lady Cowper ?, that he sawed an iron bar

through with a watch spring - especially as she describes him as "a natural

fool, or mad, though his natural character is that of a stubborn, illiterate,

ill bred brute. He has eight wives". This Lady of the Bed-Chamber was obviously

a poor judge of breeding and may well have invented the story of the watch

spring.

Unfortunately Lord Winton never made a recognised

marriage. It was alleged, by a claimant to the Earldom, that he had married

about 1710 Margaret McKlear; but this was never proved. It is however certain

from the evidence of Elizabeth Stevenson referred to above that he had by her a

son John and a daughter Christian, and from them have descended various

Seton-Winton's.

Contemporary as well as later historians have been

unfair in their estimation of the character of the

last Earl of Winton.

Thus Mackay says: "he was mighty subject to a

particular caprice natural to his family".

1, without attempting to define that

alleged defect.

One of the Counsel pleaded in Court that he was "in that doubtful state of

memory, not insane enough to be within the protection of the law nor sane enough

to do himself the least service".

Justin McCarthy too describes him as "a poor feeble creature, hardly sound in

his mind"

2 - On the other hand, Sir Walter

Scott considered "he displayed more sense and prudence than most of those

engaged in that unfortunate affair".

3 - Patten too considered that "all

his actions speak him to be master of more penetration than many of those whose

characters suffer no blemish as to their understanding" .** That Winton had a

hot temper is more than likely; it is shown in his portraits, and, as late as

1743, when Lord Elcho met him at the Jacobite Court at Rome, he was temporarily

in disgrace for having quarrelled with a gentleman, and having drawn his sword

in the presence of the exiled 'King James'.

|

The Earl fought with

great gallantry at the barricades of Preston, but was at last obliged to

surrender along with the other insurgents, and was carried a prisoner to London,

and confined in the Tower. He was brought to trial before the House of Lords,

15th March, 1716, and defended himself with considerable ingenuity. Such was the

sensation of the Earls Trial, the local Printer of the time, Daniel Bridge, was

noted for his own trial for the printing of the Earls Trial proceedings, noted

in the House of Lords Journal, Volume 20, 27th April, 1716.

The Earl fought with

great gallantry at the barricades of Preston, but was at last obliged to

surrender along with the other insurgents, and was carried a prisoner to London,

and confined in the Tower. He was brought to trial before the House of Lords,

15th March, 1716, and defended himself with considerable ingenuity. Such was the

sensation of the Earls Trial, the local Printer of the time, Daniel Bridge, was

noted for his own trial for the printing of the Earls Trial proceedings, noted

in the House of Lords Journal, Volume 20, 27th April, 1716.