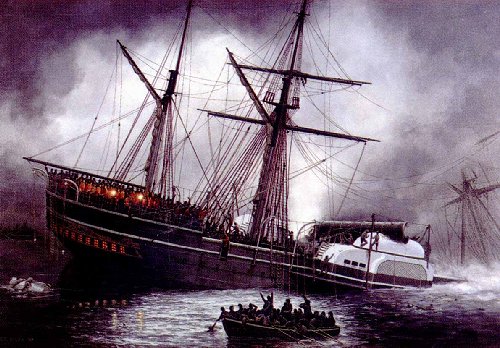

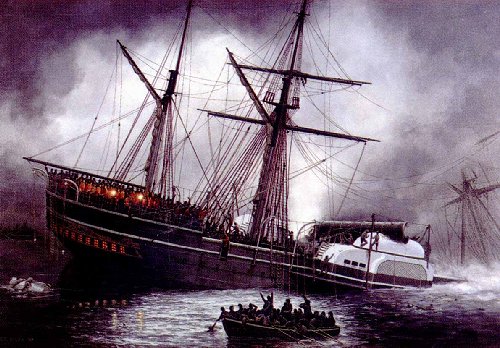

The sinking of the HMS Birkenhead,

and the heroic actions of Lieutenant Colonel

Alexander Seton of Mounie

On the 7th of January 1852, the iron paddle

troopship "Birkenhead," of 1400 tons and 556 horse-power, commanded by Master

Commanding Robert Salmond, sailed from the Cove of Cork, bound for the Cape of

Good Hope, with detachments from the depots of ten regiments, all under the

command of Lieutenant-Colonel Seton of the 74th Highlanders. Altogether there

were on board about 631 persons, including a crew of 132, the rest being

soldiers with their wives and children. Of the soldiers, besides Colonel Seton

and Ensign Alexander Cumming Russell, 66 men belonged to the 74th.

On the 7th of January 1852, the iron paddle

troopship "Birkenhead," of 1400 tons and 556 horse-power, commanded by Master

Commanding Robert Salmond, sailed from the Cove of Cork, bound for the Cape of

Good Hope, with detachments from the depots of ten regiments, all under the

command of Lieutenant-Colonel Seton of the 74th Highlanders. Altogether there

were on board about 631 persons, including a crew of 132, the rest being

soldiers with their wives and children. Of the soldiers, besides Colonel Seton

and Ensign Alexander Cumming Russell, 66 men belonged to the 74th.

The "Birkenhead" made a fair voyage out, and

reached Simon's Bay, Cape of Good Hope, on the 23rd of February, when Captain

Salmond was ordered to proceed eastward immediately, and land the troops at

Algoa Bay and Buffalo River. The "Birkenhead" accordingly sailed again about six

o'clock on the evening of the 25th; the night being almost perfectly calm, the

sea smooth, and the stars out in the sky. Men, as usual, were told off to keep a

look-out, and a leadsman was stationed on the paddle-box next the land, which

was at a distance of about 3 miles on the port side. Shortly before two o'clock

on the morning of the 26th, when all who were not on duty were sleeping

peacefully below, the leadsman got soundings in 12 or 13 fathoms: ere he had

time to get another cast of the lead, the "Birkenhead" was suddenly and rudely

arrested in her course; she had struck on a sunken rock, surrounded by deep

water, and was firmly fixed upon its jagged points. The water immediately rushed

into the fore part of the ship, and drowned many soldiers who were sleeping on

the lower troop deck.

It is easy to imagine the consternation and

wild commotion with which the hundreds of men, women, and children would be

seized on realising their dangerous situation. Captain Salmond, who had been in

his cabin since ten o'clock of the previous night, at once appeared on deck with

the other naval and military officers; the captain ordered the engine to be

stopped, the small bower anchor to be let go, the paddle-box boats to be got

out, and the quarter boats to be lowered, and to lie alongside the ship.

It might have been with the "Birkenheid" as

with many other passenger-laden ships which have gone to the bottom, had there

not been one on board with a clear head, perfect self-possession, a noble and

chivalrous spirit, and a power of command over others which few men have the

fortune to possess; this born "leader of men" was Lieutenant-Colonel Seton of

the 74th Highlanders. On coming on deck he at once comprehended the situation,

and without hesitation made up his mind what it was the duty of brave men and

British soldiers to do under the circumstances. He impressed upon the other

officers the necessity of preserving silence and discipline among the men.

Colonel Seton then ordered the soldiers to draw up on both sides of the

quarter-deck; the men obeyed as if on parade or about to undergo inspection. A

party was told off to work the pumps, another to assist the sailors in lowering

the boats, and a third to throw the poor horses overboard. "Every one did as he

was directed," says Captain Wright of the 91st, who, with a number of men of

that regiment, was on board. "All received their orders, and had them carried

out, as if the men were embarking instead of going to the bottom; there was only

this difference, that I never saw any embarkation conducted with so little noise

and confusion."

Meanwhile Captain Salmond, thinking no doubt

to get the ship safely afloat again and to steam her nearer to the shore,

ordered the engineer to give the paddles a few backward turns. This only

hastened the destruction of the ship, which bumped again upon the rock, so that

a great hole was torn in the bottom, letting the water rush in volumes into the

engine-room, putting out the fires.

The situation was now more critical than

ever; but the soldiers remained quietly in their places, while Colonel Seton

stood in the gangway with his sword drawn, seeing the women and children safely

passed down into the second cutter, which the captain had provided for them.

This duty was speedily effected, and the cutter was ordered to lie off about 150

yards from the rapidly sinking ship. In about ten minutes after she first

struck, she broke in two at the foremast-this mast and the funnel falling over

to the starboard side, crushing many, and throwing into the water those who were

endeavouring to clear the paddle-box boat. But the men kept their places, though

many of them were mere lads, who had been in the service only a few months. An

eye-witness, speaking of the captain and Colonel Seton at this time, has

said-"Side by side they stood at the helm, providing for the safety of all that

could be saved. They never tried to save themselves."

Besides the cutter into which the women and

children had been put, only two small boats were got off, all the others having

been stove in by the falling timbers or otherwise rendered useless. When the

bows had broken off, the ship began rapidly to sink forward, and those who

remained on board clustered on to the poop at the stern, all, however, without

the least disorder. At last, Captain Salmond, seeing that nothing more could be

done, advised all who could swim to jump overboard and make for the boats. But

Colonel Seton told the men that if they did so, they would be sure to swamp the

boats, and send the women and children to the bottom; he therefore asked them to

keep their places, and they obeyed. The "Birkenhead" was now rapidly sinking;

the officers shook hands and bade each other farewell; immediately after which

the ship again broke in two abaft the mainmast, when the hundreds who had

bravely stuck to their posts were plunged with the sinking wreck into the sea.

"Until the vessel totally disappeared," says an eyewitness, "there was not a cry

or murmur from soldiers or sailors." Those who could swim struck out for the

shore, but few ever reached it; most of them either sank through exhaustion or

were devoured by the sharks, or were dashed to death on the rugged shore near

Point Danger, or entangled in the death-grip of the long arms of sea-weed that

floated thickly near the coast. About twenty minutes after the "Birkenhead"

first struck on the rock, all that remained visible were a few fragments of

timber, and the main-topmast standing above the water. Of the 631 souls on

board, 438 were drowned, only 193 being saved: not a single woman or child was

lost. Those who did manage to land, exhausted as they were, had to make their

way over a rugged and barren coast for fifteen miles, before they reached the

residence of Captain Small, by whom they were treated with the greatest kindness

until taken away by H.M. steamer "Rhadamanthus."

The three boats which were lying off near

the ship when she went down picked up as many men as they safely could, and made

for the shore, but found it impossible to land; they were therefore pulled away

in the direction of Simon's Town. After a time they were descried by the

coasting schooner "Lioness,' the master of which, Thomas E. Ramsden, took the

wretched survivors on board, his wife doing all in her power to comfort them,

distributing what spare clothes were on board among the many men, who were

almost naked. The "Lioness" made for the scene of the wreck, which she reached

about half-past two in the afternoon, and picked up about forty-five men, who

had managed to cling to the still standing mast of the "Birkenhead." The

"Lioness," as well as the "Rhadamanthus," took the rescued remnant to Simon's

Bay.

Of those who were drowned, 357, including 9

officers, belonged to the army; the remaining 81 formed part of the ship's

company, including 7 naval officers. Besides the chivalrous Colonel Seton and

Ensign Russell, 48 of the 66 men belonging to the 74th perished.

Any comment on this deathless deed of heroic

self-denial, of this victory of moral power over the strongest impulse, would be

impertinent; no one needs to be told what to think of the simple story. The 74th

and the other regiments who were represented on board of the "Birkenhead," as

well as the whole British army, must feel prouder of this victory over the last

enemy, than of all the great battles whose names adorn their regimental

standards.

The only tangible memorial of the deed that

exists is a monument erected by Her Majesty Queen Victoria in the colonnade of

Chelsea Hospital; it bears the following inscription :-

"This monument is erected by command of Her

Majesty Queen Victoria, to record the heroic constancy and unbroken discipline

shown by Lieutenant-Colonel Seton, 74th Highlanders, and the troops embarked

under his command, on board the "Birkenhead," when that vessel was wrecked off

the Cape of Good Hope, on the 26th of February 1852, and to preserve the memory

of the officers, non commissioned officers, and men who perished on that

occasion. Their names were as follows:-

"Lieutenant-Colonel ALEXANDER SETON, 74th

Highlanders, commanding the troops; Cornet Rolt, Sergeant Straw, and 3 privates,

12th Lancers; Ensign Boylan, Corporal M'Manus, and 34 privates, 2nd Queen's

Regiment; Ensign Metford and 47privates, 6th Royals; 55 privates, 12th Regiment;

Sergeant Hicks, Corporals Harrison and Cousins, and 26 privates, 43rd Light

Infantry; 3 privates 45th Regiment; Corporal Curtis and 29 privates, 60th

Rifles; Lieutenants Robinson and Booth, and 54 privates, 73rd Regiment; Ensign

Russell, Corporals Mathison and William Laird, and 46 privates, 74th

Highlanders; Sergeant Butler, Corporals Webber and Smith, and 41 privates, 91st

Regiment; Staff Surgeon Laing; Staff Assistant-Surgeon Robinson. In all, 357

officers and men. The names of the privates will be found inscribed on brass

plates adjoining."

Lieutenant-Colonel Seton, whose

high-mindedness, self-possession, and calm determination inspired all on board,

was son and heir of the late Alexander Seton, Esq. of Mounie, Aberdeenshire, and

represented the Mounie branch of the old and eminent Scottish house of

Pitmedden. His death was undoubtedly a great loss to the British army, as all

who knew him agree in stating that he was a man of high ability and varied

attainments; he was distinguished both as a mathematician and a linguist. Lord

Aberdare (formerly the Right Honourable H. A. Bruce) speaks of Colonel

Seton, from personal knowledge, as "one of the most gifted and accomplished men

in the British army."

On the 7th of January 1852, the iron paddle

troopship "Birkenhead," of 1400 tons and 556 horse-power, commanded by Master

Commanding Robert Salmond, sailed from the Cove of Cork, bound for the Cape of

Good Hope, with detachments from the depots of ten regiments, all under the

command of Lieutenant-Colonel Seton of the 74th Highlanders. Altogether there

were on board about 631 persons, including a crew of 132, the rest being

soldiers with their wives and children. Of the soldiers, besides Colonel Seton

and Ensign Alexander Cumming Russell, 66 men belonged to the 74th.

On the 7th of January 1852, the iron paddle

troopship "Birkenhead," of 1400 tons and 556 horse-power, commanded by Master

Commanding Robert Salmond, sailed from the Cove of Cork, bound for the Cape of

Good Hope, with detachments from the depots of ten regiments, all under the

command of Lieutenant-Colonel Seton of the 74th Highlanders. Altogether there

were on board about 631 persons, including a crew of 132, the rest being

soldiers with their wives and children. Of the soldiers, besides Colonel Seton

and Ensign Alexander Cumming Russell, 66 men belonged to the 74th.