|

The

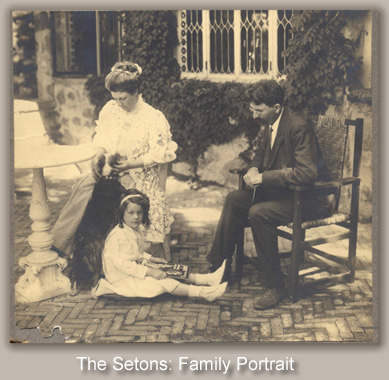

Setons at Home: Organizing a Family Biography

Lucinda H. MacKethan

Department of English

North Carolina State University

Houses are some of America's greatest storytellers and

function in any culture as powerful social symbols. The double meaning of "House," which

Edgar Allan Poe understood so well when he wrote his classic story "The Fall of the House

of Usher," demonstrates how the house-as-structure in its physical design can become a

telling statement of identity, taste, class, place, training, and heritage.

In

terms of semiotics, the study of sign systems and the conventions governing their

interactions, the house as "form" signals the symbolic as well as genealogical ligatures

of family. Poe was able with great economy in his story to expose and explore one man's

full life through intertwining descriptions of Usher's family lineage and the residence

in which he dwelled. The linguistic association of House with Nation-State is another

significant nineteenth century usage to consider, as when Abraham Lincoln, in 1858,

presented in simple domestic terms his nation's terrible dilemma: "A house divided

against itself cannot stand." Across the Atlantic, in 1860, the year that saw the United

States reach the last stage of its unalterable dividedness before the cataclysm of war,

Ernest Thompson Seton was born in the rugged Northumberland region of England. Forty

years later he was well on his way to becoming a standard bearer of a new American

century at its supremely confident beginning. To frame the story of the Seton family in

America -- father Ernest, mother Grace, and daughter Anya -- through the houses that they

themselves built between 1900 and 1951, is to have a way to contain, to "house" so to

speak, their lives -- geographically, psychologically, and socially - as successful

writers, as prominent American personalities, and as a complex and ultimately failed

family. In

terms of semiotics, the study of sign systems and the conventions governing their

interactions, the house as "form" signals the symbolic as well as genealogical ligatures

of family. Poe was able with great economy in his story to expose and explore one man's

full life through intertwining descriptions of Usher's family lineage and the residence

in which he dwelled. The linguistic association of House with Nation-State is another

significant nineteenth century usage to consider, as when Abraham Lincoln, in 1858,

presented in simple domestic terms his nation's terrible dilemma: "A house divided

against itself cannot stand." Across the Atlantic, in 1860, the year that saw the United

States reach the last stage of its unalterable dividedness before the cataclysm of war,

Ernest Thompson Seton was born in the rugged Northumberland region of England. Forty

years later he was well on his way to becoming a standard bearer of a new American

century at its supremely confident beginning. To frame the story of the Seton family in

America -- father Ernest, mother Grace, and daughter Anya -- through the houses that they

themselves built between 1900 and 1951, is to have a way to contain, to "house" so to

speak, their lives -- geographically, psychologically, and socially - as successful

writers, as prominent American personalities, and as a complex and ultimately failed

family.

The decision to use the Setons' homes as a way to organize

a narrative of their lives, a way to filter their motives and emotions, was a relatively

easy one for this biographer, although not one with an immediate logic other than sheer

visibility. Their five houses still stand. One of them, the first that ETS built, is now

a century old and just bought by the city of Greenwich to be preserved as a park. The

last of his homes, Seton Castle, rises on a bluff that provides a view of all the grand

mountain ranges surrounding Santa Fe, New Mexico, and it, too, is in the process of a

transfer of ownership that may provide public access and new interest in Ernest Thompson

Seton's phenomenal work as a naturalist and anthropologist. The house built by daughter

Anya in Old Greenwich was sold out of the family only two years ago, in 1999, leaving its

fate in peril as new owners contemplate whether to tear it down and build something more

in keeping with the grandeur of neighboring properties. The two Lake Avenue, Greenwich

properties are still privately owned residences, maintained in something close to the

same state that ETS planned for them in the second decade of the twentieth century. Lake

Avenue, Greenwich, itself seems impervious to time, its homes, long drives, hundred year

old trees, breathtaking views the epitome of a quiet, classical, exclusive, eminently

enviable but mostly inaccessible American aristocracy of wealth. The Seton family has

left its signs in books and houses, and the houses are in many ways the open book that

best reveals the architecture of their lives. To explain this idea, it will be necessary

to tell a little of the "Who" these people were, and then to ground them in the "Where"

of their homes, as a way of introducing the "Why" of this narrative.

Who were the Setons? They were first and foremost a family

of writers -- father, mother, and daughter -- who wrote book after book successfully,

often with profit and popularity somewhat more in mind than artistry. The appeal of their

books, and the popularity that resulted, were phenomena that made them relatively rich

and famous in their own time but which practically guaranteed that they would be ignored

by posterity, particularly the later twentieth century academic guardians of high

culture. The academic literati of the last forty years have not looked favorably on ETS's

animal tales, nor Grace's sprawling travel books, nor - God forbid - Anya's "historical

romances" (she vastly preferred the term "biographical novel" for most of these works,

which hasn't helped them among highbrows). Yet during their lives they were as successful

a professional family as American letters has ever produced. ETS, as he was usually known

in later years, made his fortune from his first book, the incomparable collection of

animal tales entitled Wild Animals I Have Known, published in 1898 and never out

of print since that time. He also won huge acclaim between 1900 and 1920 as a naturalist,

a lecturer, and a "leader of boys." He is honored today as the co-founder of the Boy

Scouts of America, founder of the Woodcraft League, and co-founder, with Grace, of the

Campfire Girls. Grace was no retiring, modest "woman behind the great man" herself. She

was president of the Connecticut Women's Suffrage League, organized and later commanded a

woman's mobile relief unit in France during World War I, wrote seven travel

autobiographies, and served two terms as president of the National League of American Pen

Women. (After their divorce, ETS sniffed that she was "ambitious.") The only child of

Grace and ETS, named Ann (later Anya), was unusual in both her haunting beauty and her

intelligence. Yet she never attended college, married at nineteen, and remained an

accomplished if restless housewife until her late thirties, when her dream of becoming a

writer finally came true with the publication of a first novel that, like her father's

first effort, became a bestseller. All ten of Anya Seton's historical novels were

bestsellers, most of them Book-of-the-Month Club selections, beginning with My

Theodosia in 1941 and ending with Green Darkness in 1973.

Ernest Thompson, Grace Gallatin, and Anya Seton were all three composed of equal parts

wanderer and writer, with little room, over time, for other attachments unless they could

be fit into these two. ETS, or "The Chief," as the patriarch was often known, wrote his

more than half a hundred books literally between trips, and most of them were closely

connected in some way or another to his travels to virtually every frontier in North

America. Grace Gallatin Thompson Seton authored her seven widely read travel books

between 1907 and 1937, all of them based on her own journeys, often unaccompanied except

for guides, to exotic places - the American southwest, Egypt, Paraguay, India, Indochina,

and China. It is not surprising that Grace and Ernest met on board a ship bound for

Paris, where he was returning to his art studies and she hoped to expand her career as a

fledgling newspaper columnist. Indeed, the couple seemed destined from birth for roaming

the globe. In 1866, not quite six years old, Ernest emigrated with his parents and eight

brothers from South Shields, England, to Quebec and then on to the frontier township of

Lindsay, upper Ontario.

Grace

Gallatin, born in 1872, was taken by her mother, the beautiful Clemenzie Rhodes Gallatin,

from her father's palatial home (later adopted as the governor's mansion in Sacramento,

California), to live in New York City at the age of nine, following her parents'

acrimonious divorce. Grace never knew a permanent home as a child, growing up as the

touring companion of her restless mother. Grace

Gallatin, born in 1872, was taken by her mother, the beautiful Clemenzie Rhodes Gallatin,

from her father's palatial home (later adopted as the governor's mansion in Sacramento,

California), to live in New York City at the age of nine, following her parents'

acrimonious divorce. Grace never knew a permanent home as a child, growing up as the

touring companion of her restless mother.

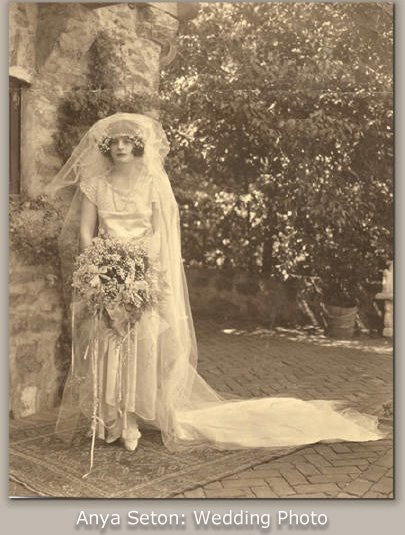

Daughter Ann probably traveled more than most upper-middle class children of her time,

but she was also frequently left at home with a series of nannies during her growing up

years, or boarded away at school. By age nineteen she was ready for flight herself, and

married a young Rhodes scholar and recent Princeton graduate, Hamilton Cottier, in the

summer of 1923. They spent their honeymoon voyage to England on the grand Adriatic (he

seasick, she restlessly roaming the decks), bound for Oxford and two years of life

abroad. Ann did not begin her most compulsive wanderings until the 1940s, when she was

fashioning her career as an historical novelist. Her first book, My Theodosia

(1941), took her to Charleston to research the lives of the South Carolina Alstons, a

planter aristocrat family that included in its ranks governor Joseph Alston, who had

married Theodosia, the lovely, doomed daughter of Aaron Burr. Following the great success

of this romantic tale, Anya Seton, by then the mother of three children from two

marriages, continued the practice of traveling for long periods around all the places

that comprised her books' settings. She once commented to her daughter Pamela that she

was unable to get an adequate sense of the places she wanted to write about without

seeing them in person. And mother Grace wrote a friend in 1944 that wherever Ann hung her

typewriter was her home. From a base in Greenwich, she visited and immersed herself in

the historical backdrops of the Hudson River, northern England and Scotland, France,

Italy, Iceland, and the American Southwest. Her ten bestsellers were meticulously set

within their historical and natural milieu, ranging from Arthurian England to the early

twentieth century silver mines of Nevada.

It is hard to say whether the Setons' writing triggered their travels, or whether their

travels triggered their writing - the two passions were so closely interwoven that one

always led to the other. The elder Setons were undoubtedly influenced as well by the

cultural wanderlust and the immigration patterns of the America of their time. Early

twentieth century Americans rich or poor spent much of their time arranging for the

packing of steamer trunks or gathering scant belongings into carpetbags. Ernest had

become a Canadian immigrant at an early age, and by the age of nineteen, in 1879, left

his parents' home in Toronto virtually for good, heading for London to pursue his twin

careers as an artist-naturalist. Before marrying at the age of thirty-six, he had won

notice from the art salons of both Paris and Chicago, he had tracked wolves in Colorado

and New Mexico, had homesteaded in Manitoba, where he learned his later famous woodcraft

habits from a Cree Indian, and had crisscrossed the Atlantic Ocean several times. With

each venture there was writing. First invariably came the meticulous and painstaking

journal documentation of the wildlife, the flora and fauna that he pursued or simply

stumbled upon. Then followed the illustrations for the books of others, such as Frank

Chapman's Bird Life (1897), and then his fiction, part natural science and part

tall tale, beginning with his collection of several magazine stories into the work that

set new standards for the fledgling genre of the animal tale, Wild Animals I Have

Known. Fame as a writer led back to more travel in a lucrative new career, that of

lecturer, beginning with ETS's first transcontinental tour in the summer of 1899.

Grace Gallatin Seton, at first content to be her husband's editor, proofreader, and

publicist, soon discovered that she too had stories to tell, and from the first, her

books were never only about traveling but also about being a woman traveler, usually with

an understanding of travel as a male prerogative. The title "A Woman Tenderfoot" might

have seemed doubly discrediting in a woman's story of trying to keep up with her husband

on a grueling trek through the Wild West, yet in Grace Seton's hands, the story made

femininity into a challenge, even an asset. It was not something to be discarded in order

to face grizzlies, rattlesnakes, or yellow jackets, but something to use to provide a

unique, intriguing perspective on the western wilderness. In all the books that followed

her first one, Grace's true subject is the woman writer herself in her quest for new

worlds to write about. The autobiographical voice suited both Ernest and Grace; their own

fascinating experiences with exotic people, places, and events proved heady fare, for

themselves as well as their readers. Thus from 1898 on, Grace and Ernest Seton

progressively shaped their private lives more and more into public story-making events,

seeking outposts of the strange, different, wild, and unknown to visualize and to conquer

by their pens. Not surprisingly in such a scheme of self-definition, home in a purely

geographical chronicle seems to figure primarily as a place to leave. |